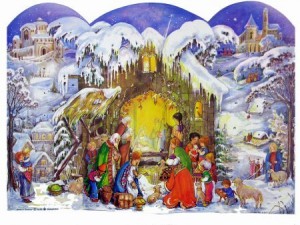

As a child I was sometimes taken to church at Christmas. I saw countless nativity scenes, both 2D and 3D. (Often, like the German advent calendar above, they linked the old Christmas story to the wintry weather of Northern Europe, where the Christian holiday has subsumed an older solstice festival.) I sung many carols (‘In the deep mid-winter, long ago, earth stood hard as iron, water like a stone….’). I heard readings from the gospels. I saw nativity plays, and even participated in at least one (I was a shepherd). I was exposed to all this, but I don’t remember at any point, even for a moment, believing the story- the virgin birth, the angels, the shepherds, the wise men – was actually true. In fact it seemed to me obvious that nobody really did believe that, just as it was obvious to me that no one really believed in Santa.

As a child I was sometimes taken to church at Christmas. I saw countless nativity scenes, both 2D and 3D. (Often, like the German advent calendar above, they linked the old Christmas story to the wintry weather of Northern Europe, where the Christian holiday has subsumed an older solstice festival.) I sung many carols (‘In the deep mid-winter, long ago, earth stood hard as iron, water like a stone….’). I heard readings from the gospels. I saw nativity plays, and even participated in at least one (I was a shepherd). I was exposed to all this, but I don’t remember at any point, even for a moment, believing the story- the virgin birth, the angels, the shepherds, the wise men – was actually true. In fact it seemed to me obvious that nobody really did believe that, just as it was obvious to me that no one really believed in Santa.

But I liked the story. I liked the way it came round every year, like midwinter itself, and I liked the way that we all came back to it together. For me, it became a story about human birth: the mystery of a living being emerging into the inanimate mineral world (‘hard as iron’, ‘like a stone’), a tiny thing, dwarfed by the great inanimate universe, but yet in a way, bigger than all of it put together. The story wasn’t true, but it brought me into the presence of a truth, allowed me to experience it not simply as a fact, but in my imagination. It allowed me to participate in it.

The value of these stories is not just a question of their literal truth or falsehood. This is what Dawkins and Co don’t get, useful as it is to have them yapping round in the yard to see off the fundamentalist crazies. The fundamentalist crazies don’t get it either.

One of the most interesting writers on the complexities of the distinction between truth and falsehood is Philip Dick: it is his constant theme. His Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, famously, is about real humans hunting down fake ones (the crucial difference being the capacity for empathy). Many of the real humans in the book subscribe to an austere religion called Mercerism, and regularly commune by electronic means with the figure of Mercer himself, forever toiling up a barren hill, while rocks and stones are thrown at him. Late in the book, this central scene of Mercerism is shown to have been faked up in a studio: Mercer, it seems, was just an actor, the hill a painted set.

But here’s the interesting part. People carry on being Mercerists anyway. The ones who exposed the hoax were androids, andys, fake humans. Their mistaken assumption that, by exposing the hoax, they’d destroy the belief system, was perhaps itself evidence of their lack of human understanding, their fakeness. Empathy and imagination, after all, are closely related things.