Interview with Paul Semel here.

Author: Chris

US release of Dark Eden

Dark Eden came out in the US and Canada yesterday!! Random House have sent me a bunch of N American blog reviews that have appeared so far, and I’ll post the links here. Haven’t read them all but the ones I have read are pretty good.

o http://pili-inlovewithhandmade.blogspot.com/2014/03/mark-this-book-monday-arc-review-of_7244.html

o http://books-forlife.blogspot.com/2014/04/dark-eden-chris-beckett.html

o http://shetreadssoftly.blogspot.com/2014/03/dark-eden.html

o http://www.fridaynirvana.com/fiction/2014/04/book-review-dark-eden-by-chris-beckett.html

o http://www.fromlefttowrite.com/tag/feed-your-reader/

o http://www.sfx.co.uk/2014/03/24/coming-up-in-the-sfx-book-club/

o http://www.giantfreakinrobot.com/scifi/giant-freakin-bookshelf-week-march-31-2014.html

o http://www.myfriendsarefiction.com/my-to-read-list-for-march

Some thoughts on world-building

Some thoughts on world-building here (guest post on Suvudu site).

Ciemny Eden

Seems the Polish version of Dark Eden has come out without my noticing! Here’s the cover.

And here is a very nice review in Polish, if Google Translate is anything to go by.

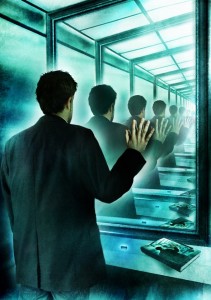

Room full of mirrors

I’ve always liked the lyrics of this song by Jimi Hendrix.

I used to live in a room full of mirrors

All I could see was me

Well I take my spirit and I crash my mirrors

Now the whole world is here for me to see

I said the whole world is here for me to see

Now I’m searching for my love to be…

It’s a hard and scary thing to give up the company of one’s own projections, and to step out into a real world which you can’t control, and in which will only ever be a small part. But unless you make that step, you will never grow up and you will be forever alone .

Roughly speaking, that’s the idea behind The Holy Machine, though the influence of this song is more obvious in Marcher, whose main protagonist actually does live in a room in a room full of mirrors.

My garden shed

My best drawing to date: my garden shed in the spring sunlight.

A rigged game

In my other life (I work part-time as a lecturer), I’ve sometimes used a rigged monopoly game – a game where one person starts off with, say, ten times as much money as the other, as a way of representing the unfairness of life. I used it in a text book too. The point I wanted to make was not only that life is unfair, but that it is so unfair that, if it was a game, most of us would refuse to play.

In my other life (I work part-time as a lecturer), I’ve sometimes used a rigged monopoly game – a game where one person starts off with, say, ten times as much money as the other, as a way of representing the unfairness of life. I used it in a text book too. The point I wanted to make was not only that life is unfair, but that it is so unfair that, if it was a game, most of us would refuse to play.

I only recently found out (thanks to Thure Etzold) that a rigged monopology game has actually been used as the basis of a psychological experiment to explore the effect of wealth on human behaviour. Paul Piff observed games of monopoly between pairs of players, randomly assigned to advantaged and disadvantated positions. Even though they knew the game was rigged to make it virtually certain that they would win, advantaged players would start to act in a more arrogant way towards their adversary. If we are doing better than another person, the experiment seems to suggest, we start to feel superior to them, even if our rational head knows that our success is none of our doing. Financial success means status, and status means we can push other people around.

This is consistent with other studies by Piff in which he found that, for instance, expensive cars are less likely to stop at pedestrian crossings than cheaper ones, and that better-off people in psychological experiments are more likely than poorer ones to help themselves to sweets that they have been specifically told are there to give to children in another study. If you haven’t come across this work, there’s a PBS video here, and an article here.

Through endless skies

My son Dom and I have a habit of sending each other interesting songs that we come across, and he recently sent me this one, ‘Planet Caravan‘ by Black Sabbath, about the singer wandering through the universe with his lover.

Listening to it reminded me of one very simple reason why I write science fiction rather than realist fiction. If you are going to make stuff up, why confine yourself to the narrow and parochial limits of our little patch of space and time?

It was twenty years ago today…

Well, maybe not today exactly, but it was about this time of the year in 1994 that I embarked on six months unpaid leave from my then job as a social work manager to write The Holy Machine. An expensive decision, which looked at the time as if it wouldn’t yield much in the way of concrete results. What I managed to complete in 1994 was a clumsy thing that I knew didn’t quite work, but couldn’t figure out how to fix. It was was to be another three years before I thought of a way to recast the book in its present form, ten years before it was first published (by Wildside in the US) and sixteen years before it was first published in the UK by Corvus. A long haul, but I’m very proud of the end result.

Join us, and you’ll be saved

One of Richard Dawkins’ Twitter homilies recently irritated me sufficiently to engage in a little tweeted debate with him and some of his followers. 140 characters don’t exactly lend themselves to nuanced discussion, however, so here are my more measured thoughts.

“As I repeatedly said [Dawkins wrote], some atheists do bad things. But it is not their atheism that drives them to it. Religion can do that.”

It’s obvious that horrific things are indeed done in the name of various religions. I think of the Taliban, the Spanish Inquisition, the Magdalene Laundries. But horrific things have also been done in the name of atheistical regimes who believed (as Dawkins does) that religion is harmful. The following is from Wikipedia, so feel free to question its accuracy, but it concurs with what I have understood to be the case from other reading.

State atheism in the Soviet Union was known as gosateizm,[2] and was based on the ideology of Marxism–Leninism. As the founder of the Soviet state, V. I. Lenin, put it:

Religion is the opium of the people: this saying of Marx is the cornerstone of the entire ideology of Marxism about religion. All modern religions and churches, all and of every kind of religious organizations are always considered by Marxism as the organs of bourgeois reaction, used for the protection of the exploitation and the stupefaction of the working class.[6]

Marxist–Leninist atheism has consistently advocated the control, suppression, and elimination of religion. Within about a year of the revolution, the state expropriated all church property, including the churches themselves, and in the period from 1922 to 1926, 28 Russian Orthodox bishops and more than 1,200 priests were killed. Many more were persecuted.[7]

And this is about the cultural revolution in China:

Marxist-Leninist ideology was opposed to religion, and people were told to become atheists from the early days of Communist rule. During the Destruction of Four Olds campaign, religious affairs of all types were discouraged by Red Guards, and practitioners persecuted. Temples, churches, mosques, monasteries, and cemeteries were closed down and sometimes converted to other uses, looted, and destroyed.[30] Marxist propaganda depicted Buddhism as superstition, and religion was looked upon as a means of hostile foreign infiltration, as well as an instrument of the ‘ruling class’.[31] Chinese Marxists declared ‘the death of God’, and considered religion a defilement of the Chinese communist vision. Clergy were arrested and sent to camps; many Tibetan Buddhists were forced to participate in the destruction of their monasteries at gunpoint.[31]

Of course there are all kinds of complex socio-political reasons why the Soviet and Chinese authorities felt the need to persecute religions (the Chinese still do, of course, notably in the case of the Falun Gong) but the same kind of thing can be said about the activities of the Inquisition or the Taliban. There’s always a political agenda and a political context for everything but if the latter can (somewhat simplistically) be described as bad things driven by religion, then it seems to me that the former can be also be described (also simplistically) not just as ‘atheists doing bad things’ but as bad things driven by atheism.

Richard Dawkins would be perfectly entitled to say that this isn’t his kind of atheism at all, and I know it isn’t. (Many Marxists, I know, would also say it wasn’t their kind of Marxism!) But in that case aren’t religious people equally entitled to say the the Inquisition isn’t their kind of religion? It’s pretty meaningless to generalise either about ‘religion’ or about ‘atheism’, since both embrace a vast range of possible worldviews, but if we are going to lump all these worldviews together into these two camps, then it really isn’t fair (though it is, unfortunately, extremely human) for one camp or the other to point to its own good guys and compare them to the other camp’s bad guys.

What I object to in Dawkins’ position isn’t atheism – I suppose I’m an atheist myself, if we have to use these simplistic categories – nor his robust critique of the unpleasant aspects of religion: I’m confident that no one who’s read The Holy Machine would suggest that I’m in any way soft on those. What I’m objecting to is the implication that ‘atheism’ (which after all just means not believing in God) is in some magical way incapable of being a pretext for bad things. This seems to me curiously reminiscent of certain of the less attractive aspects of organised religion. Join us, and you’ll be saved!

140 characters wasn’t enough, and nor is this either. The Holy Machine explores this stuff further, and I tried to critique in it a kind of intolerant literal-mindedness which can be found both among fundementalist religions and among some atheists.

None of us know the truth about the universe, not even Richard Dawkins, and we should be as generous as we can towards one another’s faltering attempts to glimpse it.