Here is the entry about me in the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (out of date on my place of work, but otherwise pretty accurate.) What an honour! I was amused by the little space kept ready for the date and place of my death.

Author: Chris

Hunger

Something reminded me of a dream I had some years ago about a young blind man. This was a real person who I had actually met in waking life, so I knew that not only was he blind and homeless, but that he had had the most awful childhood, having been rejected by his own family at an early age, and rejected since many times.

In my dream he was begging on the street. Unknown to him the cash machine in the wall behind him had broken and was spewing £20 notes out onto the pavement.

* * *

I once took it into my head to study for an MA in English Literature. For my final dissertation I wrote about a short story by Philip Dick: ‘I hope I shall arrive soon’. In the story, a man spends so many years in a state of desperation, longing to arrive at his destination, that when he finally does arrive there, he can’t believe it. He can’t be persuaded that this isn’t just another fantasy.

* * *

I bought a phone the other day which came with a single game in it called Snake Xenzia. You direct a tiny snake around the screen, picking up pieces of food. If you take it off the top edge of the screen, it reappears on the bottom. If you take it off the right, it reappears on the left. Each time it eats, the snake grows longer. The thing you have to avoid is the snake bumping into itself, at which point the phone vibrates sickeningly with the impact and the snake dies.

As the game progresses the screen becomes fuller and fuller with the snake’s coils, winding back and forth across the screen and in and out across its edges. If it is to continue to feed itself, the snake must negotiate an ever-growing labyrinth constructed of its own body and its own past.

Enchanted objects

I saw the recent movie of The Great Gatsby. Visually I found it a little lurid, but I was interested by the story and I went on to read the book, which was already sitting there on our shelves.

I saw the recent movie of The Great Gatsby. Visually I found it a little lurid, but I was interested by the story and I went on to read the book, which was already sitting there on our shelves.

What had particularly struck me in the film – it is actually surprisingly faithful to the book – was the image of the little green light burning across the bay. It is the light at the end of the landing stage of the mansion of Gatsby’s lost love Daisy.

There is a brilliant moment, after Gatsby has met up with Daisy again, where the narrator wonders if Gatsby has noticed that the green light will never again have the same meaning:

‘If it wasn’t for the mist we could see your home across the bay,’ said Gatsby. ‘You always have a green light that burns all night at the end of your dock.’

Daisy put her arm through his abruptly, but he seemed absorbed in what he had just said. Possibly it had occurred to him that the colossal significance of that light had now vanished forever. Compared to the great distance that had separated him from Daisy it had seemed very near to her, almost touching her. It had seemed as close as a star to the moon. Now it was again a green light on a dock. His count of enchanted objects had diminished by one.

High Speed Train?

I recently read Dambisa Moyo’s book Winner Take All. It’s about the coming global problem of scarcity in many key commodities (land, water, oil, copper…) and how China is steadily getting ahead of the game.

It’s an interesting book raising many different questions, but there was one thing in particular that struck me about this emerging superpower with its dynamic economy, its strategic vision and its immense energy. Although we are fond of observing that communist China is now ferociously capitalist, I learnt that most big Chinese companies are still wholly or largely state-owned.

We have been encouraged for so long to think of state-owned industries as slow, sclerotic and sleepy compared to their privately-owned counterparts – even the British political party that once stood for public ownership has become as enthusiastic a privatiser as its Conservative opponents – that this came as a shock.

I was in a train at the time, a smart double-decker high speed train zooming south across France. The train – it was unlike anything we have in the UK – was operated by SNCF, the French state-owned rail company. And I remembered how we in Britain were told that our railways had to be privatised in order to be able to get the investment in new technology that they needed.

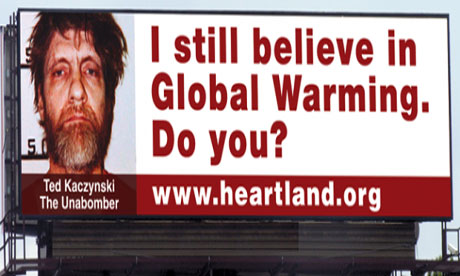

The deniers play their trump card

Now listen up all you deluded believers in the evidence of scientific research. This proves you’re wrong!!!

(See earlier post.)

The Burning Question, by Mike Berners-Lee & Duncan Clark

If you are looking for an introductory book on the climate crisis, this is as good as any I’ve read. It sets out the issues in a clear and focussed way, and tours the science, politics, psychology and economics of the subject, as well as providing an overview of the options for the future.

If you are looking for an introductory book on the climate crisis, this is as good as any I’ve read. It sets out the issues in a clear and focussed way, and tours the science, politics, psychology and economics of the subject, as well as providing an overview of the options for the future.

Several things stand out for me after reading this book. One is that doing something about climate change isn’t just a question of developing alternatives to fossil fuels. Our appetite for energy is such that we are quite capable of developing renewables and still consuming more fossil fuels than ever.

So we don’t just need to develop alternatives to fossil fuels, we need to set a limit to the total amount of fossil fuels we use. This means leaving a lot of the world’s known reserves of coal and oil permanently in the ground. No wonder the people that own them are unhappy!

Another thing that stood out (and this of course is linked to my previous point) is the dishonesty and virulence of the multi-million-dollar climate change denial industry. ‘They call it pollution. We call it life,’ said one US TV ad, as if anyone had called carbon dioxide ‘pollution’, or denied its importance to life. Another billboard campaign by the Heartland Institute

showed mug-shots of serial killers alongside the words: ‘I still believe in global warming. Do You?’ Heartland’s president, Joseph Bast, said on the accompanying press release, ‘The most prominent advocates of global warming aren’t scientists. They are Charles Manson, a mass murderer; Fidel Castro, a tyrant; and Ted Kaczynksi, the Unabomber. Global warming alarmists include Osama bin Laden, and James L. Lee.’

The savagery and cynicism of this, not to mention its utter weirdness, is fairly scary (see also Tom Burke’s piece on this here), but perhaps there’s some hope to be found in its sheer desperation? It suggests (doesn’t it?) that the deniers are pretty worried, don’t really believe they have a real argument, and don’t necessarily think they’re going to win.

Which of course they won’t. Because ultimately we’ll either do something about the problem, or find out the hard way just how wrong they were.

I recommend this book.

On being boycotted

A reader (John) disliked my recent post about the Trayvon Martin case, saying that my summaries are missing some key points. ‘Ugh,’ he begins! He says he enjoyed Dark Eden but doubts if he’ll read any of my other books, and he advises me to keep my opinions to myself:

I have never understand why athletes, public figures and those that depend on the support of a broad audience interject their political/cultural opinions into the public arena. They just anger 50% of people who may otherwise purchase their product.

Two things about this I found a bit depressing.

Firstly, the idea that I should conceal my views on politics and culture in order to get people to ‘purchase my product’, particularly since my ‘product’ itself deals with politics and culture. I find that a bit ‘ugh.’

Secondly, the idea that we should avoid the work of writers whose political or cultural views we disagree with. A book that hugely impressed me when I first read it as a teenager was Robert Heinlein’s The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, the book about a libertarian lunar society whose motto was TANSTAAFL (There ain’t no such thing as a free lunch). I didn’t agree then, and I don’t now, with Heinlein’s Tea Partyish politics, but it didn’t stop me appreciating, and wanting to emulate, the brilliance of the world-building.

One of the first accolades I received for Dark Eden was the book being selected as the ‘Big Read’ for the Greenbelt festival, and being asked to go there and give a talk about it. This is a Christian festival, and I made no secret of the fact that I am not a Christian, but people were still interested in what I had to say about the Eden story, even though it obviously meant very different things to them than it does to me. And God bless them for it!

* * *

In fairness to John, though, when I look back at my post, I can see it is unbalanced. Clearly there was some kind of fight or scuffle between Trayvon and the man who shot him, and I can see that, given the bizarre context of a country where it is okay to carry a gun, it is possible to argue that self-defence was a factor in the shooting.

But why not also, then, in the case of Marissa Alexander, who fired a shot which didn’t even hit anyone? Of course I don’t know the detail of the cases, but I find it hard to imagine any additional detail that would justify a twenty year sentence in the latter case, if a complete acquittal was justified in the former.

There are many studies that show how, in predominantly white societies, the behaviour of black people is much more negatively connoted than the same behaviour by white people. Look at this video which compares the reactions of passers-by to a young white man who appears to be stealing a bike, and then to a young black man doing exactly the same.

Hell on a handcart (2)

This is one of more bizzarre examples I’ve come across of hostility towards doing anything about climate change. Here, in the Times, Tim Montgomerie doesn’t deny that climate change is a fact, he just thinks we can’t afford to do anything about it.

Roughly speaking, his argument seems to be that, yes, the ship is sinking, but we can’t afford to use power on pumping it out, or it’ll slow down the engine.

Why doesn’t he work out the costs of not doing anything?

Going to hell on a handcart

I was pretty staggered to learn that our use of coal in the UK is now actually on the increase.

Given everything we know about global warming, its causes and its consequences for our own children and grandchildren, this is a bit like discovering that, while supposedly fighting a war on terrorism, we were actually busy funding Al-Qaeda.

All those movies where the hero saves the world from an existential threat, and then a real threat comes, and we just shrug and sleepwalk towards it!

Rats, wolves, bears

Someone told me recently that rats pair off for life and that male rats are closely involved in the care of their young. The term ‘love-rat’ turns out to be poorly chosen. Rats are faithful husbands and conscientious dads.

Another animal I’ve always thought we’ve got wrong is the wolf. Countless fairytales have encouraged us to think of wolves as dark, sinister, uncontrollably violent. We use the words wolfish, vulpine. And when we imagine wolves in human form they are savage and murderous.

But why? On what evidence?

I’ve sometimes thought of writing a story in which a real wolf-man is created with the body and intelligence of a human, but the instincts and drives of a wild wolf. To everyone’s disappointment, he turns out to be a mild-mannered, comformist creature, anxious to please, concerned about his social standing and willing to do what he’s told.

Wolves are social, hierarchical creatures, after all. Their desires and priorities are like our own. It’s not a coincidence that they’re the ancestors of our best-loved pet. With added intelligence and a human body, wolf-man is pretty much an average bloke.

But in my story there’s also a bear-man, and he’s another thing entirely. Having the instincts of a solitary hunter, he has no need for company of any kind, except for occasional sex, and cares nothing at all for what people think of him. In my story, bear-man is capable of calculation and learning, and so assumes some sort of veneer of human-ness because he perceives it to be in his interests to do so, but beneath it he remains utterly unreachable and entirely cold. A truly scary being.

Oddly enough, though, the bear is much more positive figure in human culture than the wolf. Think of Winnie the Pooh, Paddington, Baloo, Yogi, and try and find even one wolf equivalent. Bears are seldom the villain in stories, in spite of the fact that killings of humans by bears, unlike killings by wolves, really do quite regularly occur.

Is it their very similarity to us that makes wolves our animal of choice when we want to project our violent impulses onto some other creature?

(We’ve got more than a little in common with rats too: versatile omnivores which have managed to spread themselves across most of the planet.)