Interview here, mainly on the process of writing and getting published. Thanks Zeroflash!

Blog

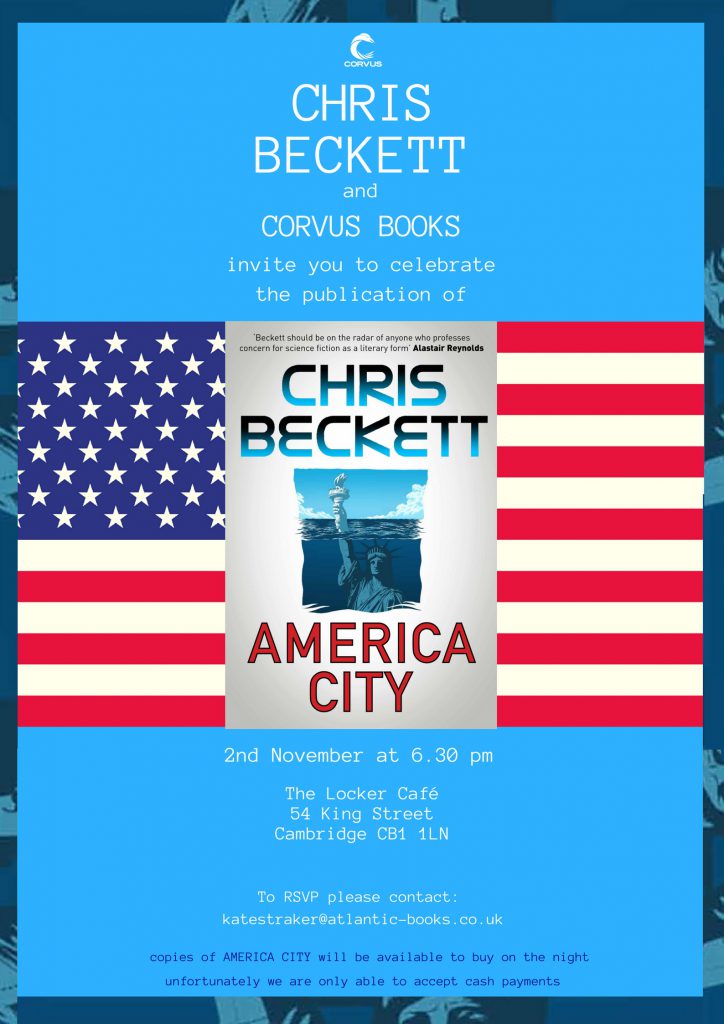

Launch of America City, Nov 2nd

If in or near Cambridge on Nov 2nd, do come to the launch of America City at the delightful The Locker Cafe on King St. (Please RSVP to Kate Straker as per invite below, so she has an idea of numbers)

Feed (Words I don’t like #3)

Here’s another word I don’t like: ‘Feed’, used in the internet sense, as in ‘there are a lot of angry people in my Twitter feed today.’ It always jars when I come across it. But the odd part in this case is that it’s actually quite an expressive word to use. What grates with me, now I think about it, is its use in an unironic/uncritical way.

In fact I’d go as far as to say that, if nobody used it in this unironic way, I might choose it myself. It has a suitably industrial and impersonal feel. It makes me think of a machine that dispenses food pellets at timed intervals to animals in a battery farm. If had not already been stripped of those connotations, it would do the job pretty well.

See also Problematic (#1), Heft, Grin (#2)

Words I don’t like #2

There are some words that I think of as typical creative writing words and have never liked. Words that, to me, say, ‘Hey look at me, I’m writing!’ I’ve never liked the word ‘heft’, for instance, as in ‘he felt the heft of it in his hand.’ It means ‘weight’ doesn’t it? Why not just say ‘weight’? No one says ‘heft’ in ordinary speech.

Another one, very unfairly, is ‘grin’, used as a more interesting alternative to ‘smile’. A perfectly ordinary word, I know, and I do choose it occasionally if I find I’ve used ‘smile’ too often, but I really don’t like it and put ‘smile’ wherever possible. ‘Grin’ feels to me, for some reason, like one of those words you fall back on in desperation when you’re trying to bring alive a character on the page who doesn’t even feel alive in your head.

The fire from the skies

When I was a kid at school in the 70s a lot of the music we listened to was blues-based stuff and prog rock. I don’t listen to much of that now -the music from then that stands the test of time for me is from quite different genres- but here is a little prog rock classic that still works for me: the extended piece by Genesis called Supper’s Ready. I specially love the section that breaks out at about 15:30 in a burst of sheer exultant energy, with imagery straight from the Book of Revelations:

With the guards of Magog, swarming around

The Pied Piper takes his children underground

Dragon’s coming out of the sea

Shimmering silver head of wisdom looking at me

He brings down the fire from the skies

You can tell he’s doing well by the look in human eyes

Better not compromise, it won’t be easy

666 is no longer alone

He’s getting out the marrow in your backbone

And the seven trumpets blowing sweet rock and roll

Gonna blow right down inside your soul

Pythagoras with the looking glass reflects the full moon

In blood, he’s writing the lyrics of a brand-new tune

Why is it that the destruction of everything we know can be such an exhilarating idea? Is too fanciful of me to say that being human is only one thin layer of what we are, and that (as the Jeff folk put it in Eden) before anything else, we are simply the world looking out at itself? From that perspective, after all, nothing can ever be finally destroyed, only thrown in the fire to be cast anew.

What SF is good for

There is a lovely review of Mother of Eden here. The reviewer, Kevin Elliot, writes ‘”Mother of Eden” is a prime example of how science fiction can handle issues which might pose problems for other genres.’

Well, I’m not the one to say whether Mother of Eden is a prime example of that or not, but I completely agree with him that science fiction is the ideal medium for exploring certain kinds of issue. As I have said elsewhere, science fiction differs from conventional realist fiction in that, while the latter holds the world constant but makes up characters and situations, science fiction makes up the world as well. This means that, while realist fiction is rich in potential for thought experiments about human psychology and human relationships, science fiction offers additional options for thought experiments about society, social structures and social change. The Eden books, for better or worse, are one such experiment.

The realist author takes the existing world (present or past) as given, in other words, but engages in the game of ‘what if’ with characters and their interactions, while SF writers can also engage in ‘what if’ games in relation to the world as a whole. In the case of Eden, I asked myself, ‘what if society evolved all over again from two individuals.’

I’m talking about potential here. Not all science fiction carries out such experiments – the SF pack of playing cards can be used for many different games – and, of course, when it does, it doesn’t necessarily do it well. But this is true also of the realist pack of cards.

Heil Trump!

We have had neo-Nazi marches before, in Europe and America. But here is one where marchers are chanting the name of the US President as if he were their leader. That, surely, is unprecedented.

Video: Alt-right marcher shouting "Heil, Trump" while waving nazi salute

via @tomperriello #charlottesville #AMJoy pic.twitter.com/s3MMSxEhWe

— Scott Dworkin (@funder) August 12, 2017

Long and cut, or short and add?

I’ll be at Worldcon 75 in Helsinki next week, and I’ve been asked to take part in a panel on ‘Write Long and Cut, or Write Short and Add? (Is it better to write as much as possible and then edit out, or vice versa?)’. If you’re at the con, I hope I’ll see you there! In the meantime, here are a few thoughts:

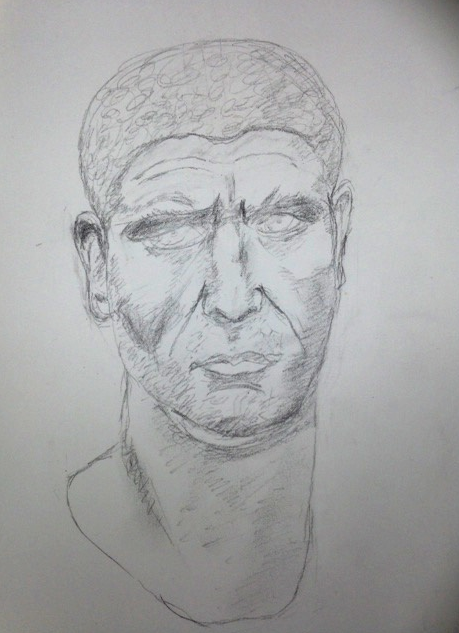

I’ve been doing a bit of drawing lately (one of my recent efforts is below) and one of the things I’ve learnt about that is that you need to be careful to get the basics right before you commit too much to the detail. If you are drawing a face for example, no amount of detail will make the picture look like its subject if the overall shape is wrong. The temptation is to get too engrossed in, say, the shadows around the eyes, only to realise later on that the eyes are too close together, and that at least one of them will need to be rubbed out completely and drawn all over again.

(Roman Emperor, Philip the Arab, drawn at Museum of Classical Archaeology, Cambridge)

(Roman Emperor, Philip the Arab, drawn at Museum of Classical Archaeology, Cambridge)

When writing fiction, there is a similar danger of over-committing to detail at too early a stage. This can result in beautifully crafted scenes which turn out not to fit in, but which you are reluctant to cut because you like them and have committed a lot of time to them: a lot more time can be wasted trying to make the book fit the scene rather than vice versa.

A big difference between drawing from life and writing fiction, though, is that there is no external object to act as a guide: you are not trying to reproduce something in front of you, but rather you are tapping into your knowledge, experience, and subconscious to create a new object that didn’t previously exist. Quite often, the overall shape may actually emerge out of details.

My novel Daughter of Eden, for instance, only came alive for me when I decided to tell the whole thing from the point of view of Angie Redlantern, and for that to happen, I first needed to bring Angie alive for myself by working over scenes told in her voice. Similarly, early drafts of The Holy Machine felt to me they were missing a certain something until I worked out how to write the opening pages. In both cases it was the detail of the voice, and how that voice described its world, that were the key to the entire book. I could have drafted out all the plot outlines I liked, but without knowing how the story was to be told, they wouldn’t have come to anything.

So it is a matter of writing something that vaguely resembles the story that I want to write, or the beginning of that story, and then working and reworking the material until it starts to feel lively. I always start a writing day by revising what I wrote on the previous day, and not infrequently I will go right back to the beginning and revise everything I’ve written so far before carrying on. It’s slow, but it seems to be necessary in order to dig myself down into the story.

As to whether to ‘write long and cut, or write short and add’ I don’t have a straightforward answer. What I’ve noticed is that, as a piece of writing develops, my sense of the centre of gravity of the piece gradually changes and I start to notice what I think of as expansion points and contraction points. In early drafts of the first half of Daughter of Eden, the story was told from multiple viewpoints like the other Eden books and Angie was simply one of several main characters. As I worked and reworked it, I decided Angie was to be at the centre of it, and that all the foregrounded characters were going to be women (Angie, Mary, Trueheart, Starlight and Gaia), while the stereotypically ‘male’ story of war and fighting would be pushed some way back into the mix.

So expansion points are places in the text which seemed of relatively minor importance to start with but are now more important, perhaps to the point where they now feel like the story. In some cases, material which was little more than a connector between two scenes, can turn out to be more important than the scenes themselves. One set of expansion points in Daughter of Eden concerned the Davidfolk’s rituals around circles and the idea of homecoming. That stuff was just a detail at first, one of those things you put in to make a scene a bit more concrete, but it became absolutely crucial to the overall shape of the book, and so I expanded and developed all that, not only by including more detail (the circles, the song, the dots on the foreheads of guards…), but by incorporating those ideas and beliefs into Angie’s thinking.

Contraction points, on the other hand, are places in the text whose importance, or necessity, has diminished over time, so that they need cutting back, or cutting out entirely. In the case of Daughter of Eden this included scenes seen from the viewpoint of male characters, some of which I cut altogether, while others were shortened and retold as observed by Angie, or reconstructed by Angie thirdhand from stories told by others, or relayed by Angie from scenes that Starlight participated in and told her about.

So I suppose my conclusion from all this is, write what you can, and be prepared both to expand and cut.

Parentless (2)

Following previous post (‘Parentless‘) about grief, and about the absence of grief where it might be expected, I had this dream about my late father. I was on a walking trip with him in Andorra (I did go on a couple of such trips with him in my late teens, though not there.) At some point we were sitting round a table with a number of other people. There were two young women sitting near me. They were there in some kind of professional capacity: they could have been publicists for a publishing company or something like that. My father was on the opposite side of the table, looking fit and youthful, talking to the people he was sitting with.

‘Not bad for someone who was completely incapacited with dementia not long ago,’ I observed to the two young women. And then a thought occurred to me. It wasn’t just dementia he’d had. I’d been at his funeral!

‘Oh I see,’ I said. ‘This must be a dream.’

I was at that particular level of consciousness where you know you are dreaming but are still not entirely clear about the implications of that. I hadn’t fully grasped that the fact I was dreaming meant that the table and the two young women were figments of my imagination. The women shrugged, completely unimpressed, but in my dream I wept.

* * *

Oddly, now I’m thinking about it, I’m reminded of a dream I had a very long time ago -perhaps as far back as my teens- when he was still alive. In my dream I was attending a funeral service for him being held at St Mary’s Church in Oxford. The church was full. The procession had passed down the aisle. And then my father himself arrived, unnoticed by anyone, and slipped into the pew where I was sitting, as if he was just another member of the congregation who’d been held up.

Who?

If it had been Inspector Morse, I would have understood. Morse is a man, and he has the hang-ups and preoccupations of a man of his age and generation. If a woman actor were to take over the role, it would no longer be the same character. Unless you decided to introduce some sort of complicated plot rationale for the switch – Morse realises he’s suppressing his feminine side and ends up having a sex change… Morse’s Oxford turns out to be a computer simulation and Morse an avatar whose characteristics can be be chosen at will…- you might just as well give the woman detective a new name and start a new series.

But Dr Who? This is a character who is not even human, well-known for regenerating himself from time to time in an entirely new body. This is a show where ‘What’s the next regeneration going to be?’ is a long-established part of the fun. How can it be anything other than an entertaining new twist if he now regenerates as a she? It’s great that the number of famous shows with female protagonists has increased by one, and it’s lovely to see the delight of fans, such as my friend Una McCormack (see her wonderfully exultant piece here!), but, even if I leave all that completely aside and just look at this ‘professionally’ as someone who’s in the business of telling stories, it seems such an obviously fruitful move to make.

But I’m interested by the voices raised in anger and disappointment -The show has been ruined… This is no longer the Doctor… I can never watch it again… – and the underlying assumption about gender that these cries imply. I may be in minority here, but I actually don’t think they are all necessarily misogynistic (at least not in the strict sense of the word, which means ‘woman-hating’). What they do imply, though, is a belief in the existence of an absolute rift between the genders, as if male identity and female identity were not just a matter of being raised with a certain set of social expectations, or even a matter of having been born with a particular kind of body or body chemistry, but went all the way down to the very foundation of identity, wherever that might be, like letters through a stick of rock: The Doctor can change his face, his body, his personality, his apparent age, and still remain the Doctor, but if he changes gender he cannot be the same person.

It’s the same kind of worldview that leads certain religious people to insist that, even though God has no body, is prior to society and biology, makes all the rules, God can nevertheless be, in some way, immutably male. (And, in a sense, it’s a view that’s embedded even in our language. In most contexts, if you want to refer to a person with a pronoun, you have to choose he or she. I only got round that a couple of sentences ago by using the word ‘God’ twice!)

Why should this one characteristic among all others be so fundamental? Some species grow up male or female depending on the temperature, others change sex from male to female in the course of their lives, others again are both simultaneously. My own experience when writing a female character such as Angie Redlantern is that what I need to do is dive down to a point that is prior to male or female and then swim upwards again in a different direction. It’s a number of layers down, that point, but nothing like as deep as many seem to think.

I wonder what would have happened if it had been a change of race?