Here’s an interview with Jason Cooper, who is a broadcaster, journalist, poet and academic among several other things. Thanks, Jason, for the interesting questions.

Blog

Eight years old again

Interview here with My Bookish Ways. Nice questions, including what book would I most like to experience again for the first time.

Freedom is slavery

Politics is a rough business everywhere but, from this side of the Atlantic, the tone of political discourse in the US can sometimes look particularly ugly. One of the worst examples I’ve ever seen, was the suggestion by Senator Rand Paul that a right to free health care is equivalent to a belief in slavery. The quote in question was the following:

With regard to the idea of whether you have a right to health care, you have realize what that implies. It’s not an abstraction. I’m a physician. That means you have a right to come to my house and conscript me. It means you believe in slavery. It means that you’re going to enslave not only me, but the janitor at my hospital, the person who cleans my office, the assistants who work in my office, the nurses.

Basically, once you imply a belief in a right to someone’s services — do you have a right to plumbing? Do you have a right to water? Do you have right to food? — you’re basically saying you believe in slavery.

I’m a physician in your community and you say you have a right to health care. You have a right to beat down my door with the police, escort me away and force me to take care of you? That’s ultimately what the right to free health care would be.

(If you think this must be some crude spoof, by the way, here is a clip of him saying it.)

By way of information to US readers, we have a free National Health Service here in the UK, meaning that everyone has a right to healthcare, and my mother and my maternal grandfather both worked for it as doctors. They were not forced to be doctors, and they were not forced as doctors to work for the state. They were paid well enough to lead prosperous middle class lifestyle. They were free to resign whenever they wanted. They could go and work for private healthcare agencies, if they prefered, or for themselves. There’s absolutely no sense at all in which their condition could be described as slavery, or indeed as different in any fundamental way to the condition of anyone else who works for an organisation of any kind. When you think what slavery actually means (and the Senator represents the former slave state of Kentucky, so he should know), the very comparison is obscene.

You might say that US politics is not my business. But actually it is because the US is a global superpower, and what happens in the US matters everywhere, and perhaps especially in the UK, where there is a common cultural heritage, and no language barrier to filter us from its blast. However I freely admit I know very little about the personalities involved, and almost nothing about Senator Paul. So here are a couple of questions.

Is Senator Paul an extremely stupid man, so lacking in curiosity that he hasn’t bothered to look into the many free health services around the world, and so lacking in imagination that he can’t figure out for himself how such a service might work without breaking down doctors’ doors?

Or is he cynical and mendacious man, who in order to serve his own political ends, tries to besmirch something that, whatever its snags, is basically benign (a community agreeing to club together to provide healthcare for everyone) by equating it with something that is evil and foul?

Echoing in the back of my mind are the slogans of George Orwell’s Oceania: WAR IS PEACE. FREEDOM IS SLAVERY. IGNORANCE IS STRENGTH. Not an exact parallel of course, but what Orwell was warning about was the misuse of language to destroy our capacity to think.

The Penfield Mood Organ

Here’s a guest post I did for Tor.com about why I love Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

(For some more extended thoughts of mine about Dick, there’s also another post here).

The benefits of imagined worlds

Another guest post here on Suvudu.com. It may seem to contradict what I said in a previous guest post on SF signal, but I don’t think it really does. And anyway, consistency is for bureaucrats and social workers as (I think) Michel Foucault observed somewhere.

Oh, wait a minute, I am a social worker!

Mother of Eden interview

Here is an interview with Paul Semel about Mother of Eden. (Many thanks, Paul, for your interest.) Paul also interviewed me last year about Dark Eden, and that interview is here.

Incidentally Mother of Eden is out in the UK on June 4th (in spite of some slightly confusing statements on Amazon UK, which the publishers are currently fixing). It’s out in the US this week.

In the picture I’m standing on a Roman road outside Cambridge, where I go to walk our dogs. Sort of appropriate really, in a book which talks a lot about living among the residue of the past.

Invisible electors

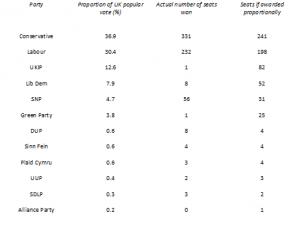

One thing that strikes me about the results of the UK election is the arbitary relationship between the number of seats won by each party, and their proportion of the popular vote. The Scottish National Party is now the 3rd largest party in the UK parliament, with 56 seats, but it did this on the basis of 1.5 million votes, while the Lib Dems, with 2.4 million votes, only got 8 seats. Even more bizarrely, the largest Northern Ireland party, the DUP, also won 8 seats, but did so with only 184,000 votes (the same number of seats as the Lib Dems, but less than a tenth of their votes). Meanwhile the Green Party, with eight times as many votes as the DUP, came out of the process with only one seat.

Suffering a brief attack of geekery, I’ve just done the sums (see table below). If seats were awarded proportionally, the Greens would have won 25 seats, the SNP 31, and the Lib Dems 52. The most spectacular difference, though, would have been that UKIP, with 12.6% of the popular vote, would have won 82 parliamentary seats, as opposed to the single seat which it actually won*.

I can’t say that I’m personally sorry that this particular outfit has not got those 82 seats. But, all the same, I can’t help thinking that the lack of relationship between votes cast and MPs elected is one of the causes of cynicism about the democratic process.

What we have at the moment is a system which rewards parties that have concentrated powerbases in particular geographical areas (like the DUP and the SNP, but also Labour and Conservatives, with their heartlands respectively in the big industrial cities and the leafy suburbs and shires). But it punishes parties whose support is more widely and thinly distributed across the country, and so grossly misrepresents the relative strength of opinion in the country in general, to the point where whole swathes of electors are rendered virtually invisible.

The fact that the SNP won all but three seats in Scotland, for instance, gives the impression that the whole of Scotland is fervently nationalist, though in fact the SNP only won half the Scottish votes, leaving the unionist half of Scotland almost completely unrepresented. (And who would have thought, from the coverage of the result that the disgraced and humiliated Lib Dems actually won 900,000 more UK votes than the proud and triumphant SNP?)

A proportional system would still, just, have yielded a right-of-centre majority, based on the popular vote in this election, with Conservatives, UKIP, DUP and UUP between them winning 329 seats, but it would have been a smaller and much more precarious majority than the one the Conservatives won on their own under the first-past-the-post system. There are lots of downsides of PR, but surely the benefit would be that there would be less triumphalism, fewer spurious claims to have the backing of “the people”, and a more transparent process of negotation between parties that represent the enormous diversity of views that actually exist?

*Of course, these figures assume that everyone would still vote for the same party under a PR system. In fact, supporters of smaller parties often decide to vote tactically for parties they think likely to win. My guess is that under a PR system, the Green Party would actually have won quite a lot more than 25 seats, because a lot of potential Green voters voted Labour this time round. No doubt this would be true of UKIP sympathisers too, many of whom probably voted Conservative for similar reasons.

*Of course, these figures assume that everyone would still vote for the same party under a PR system. In fact, supporters of smaller parties often decide to vote tactically for parties they think likely to win. My guess is that under a PR system, the Green Party would actually have won quite a lot more than 25 seats, because a lot of potential Green voters voted Labour this time round. No doubt this would be true of UKIP sympathisers too, many of whom probably voted Conservative for similar reasons.

Mother of Eden en Francais

I’m delighted to say that Presses de la Cité (who already publish the French version of DARK EDEN) have acquired French rights in MOTHER OF EDEN.

Mother of Eden Q & A

Here’s a short Q & A that the US publishers (Broadway) did with me for Mother of Eden:

1. The protagonist of Mother of Eden is a headstrong, determined young woman named Starlight Brooking, who brings about huge changes in society around her throughout the course of the novel, ending up as a truly revolutionary figure. Did you make a conscious decision to have a female protagonist? What is the role of female characters in science fiction in general, and has that changed over the years?

I guess as a writer, one tends to default to viewpoint characters who are a bit like yourself. Well, I know that’s true of me anyway, and so I make a conscious effort to try and develop main characters who are different. John Redlantern, in Dark Eden, while male, was unlike me in that he is very much a doer: someone who must be constantly on the go in order to feel alive. (This really isn’t me at all! I’m very good at doing nothing!)

Given that the protagonists of all my novels, and the majority of my short stories, had been men, I decided that it was about time I wrote a novel with a female main protagonist. In fact Starlight is female and a doer. (She’s also less than half my age, but this is common for my characters. I don’t seem to have done with that time of life!)

I like Starlight as a character. Others will have to judge of course, but, apart from that first little conscious effort of choosing a female protagonist, I didn’t find it hard to write from her perspective. Then again, I have three sisters (no brothers), two daughters, a mother, a wife, women friends, and I have worked most of life in a profession which is 85% women. If I’ve being paying attention at all, I really ought to be able to describe things from a women’s perspective!

As the book developed, it became increasingly about women too. As in Dark Eden, the story is told by a number of different people and, at one point I thought of having only women as viewpoint characters. In the end, although most of the viewpoint characters are women (Starlight, Glitterfish, Julie, Quietstream, Lucy…), I did include two men: the gentle Greenstone, and the brutal Snowleopard.

I am sure that most of the science fiction I read growing up in the seventies was (a) written by men, and (b) had men as main characters, with women mainly present as objects of love and desire. I think SF has moved on from that, thank goodness. However it does strike me that we are still better in SF at writing about tough male and female protagonists acting in stereotypically “masculine” ways, than we are at writing about people (men or women), who are gentle and nurturing in stereotypically “feminine” ways. I think that’s something to think about. After all, we need nurses and teachers at least as much as we need soldiers and atomic scientists, and I would say a good deal more so.*

2. Mother of Eden has so much to say, as Dark Eden did, about how civilizations develop and the sacrifices we make in the process. Did you start with certain issues that you wanted to address, or did those come naturally as you wrote the novel?

Well, both. I think the content of this book flowed naturally from Dark Eden, and some basic themes were certainly there in my mind from the beginning. But new themes and ideas emerged as I went along.

In Dark Eden, I showed a society that was becoming increasingly dominated by men, and increasingly controlled by violence. I knew from the beginning I wanted to think about how that developed. In Mother of Eden, the followers of David and the followers of John have created two hierarchical, militarized and male-dominated societies (a description which, of course, would still fit most of the societies on Earth today). However in both societies, there persists a folk memory of the time when the whole human community of Eden was a single family in which the central figure was a woman. (I think this is also true for most of us on Earth today: most of us grew up in an environment in which a woman was the dominant figure, our primary source of nourishment and comfort and safety, insofar as we had these things at all). Even in these male-dominated societies, it seemed to me, women still had immense power, and men, afraid of this power, had tried to channel and control it in various ways to make it serve their purposes. Gela’s ring, which Starlight puts on her finger, became a focal point for a lot of my thinking about this.

Something that emerged as a theme as I went along was power more generally. Not just men’s power and women’s power, but power itself: what it is, where it comes from, what you have to do to get it.

Another theme, that was of course present in Dark Eden also, is our relationship with the past. Now of course, the story of Dark Eden is itself the past, and we have two different societies whose enmity is based on their different takes on the meaning of those events, much as (for example) the enmity between Sunni and Shi’ite Muslims in the world today is a continuation of a quarrel that goes back to the eighth century.

As to the sacrifices we make in order to progress, yes this remains a big theme in this book. I am struck by the idea that every human society is a kind of compromise. To get one thing, we have to give up another. There is always a price for everything, it seems to me. This means that if you want easy answers, or comforting messages about how one day everything will all be wonderful, then I’m not the person to come to! I guess if I had an easy answer, I wouldn’t be writing novels!

3. Mother of Eden takes place 200 years after the events of Dark Eden. How did you decide which changes would have taken place in that time? How has the language changed as the inhabitants of Eden have lived there over the decades?

The decisions you make when writing a book of this kind are always a compromise between realism and what works for the story. I did not make major additional changes to the language, over and above those made in Dark Eden, because I didn’t want to make things too difficult for the reader, but I tried to give some sense of the fact that geographical dispersal has meant that people in Eden no longer speak a single dialect but several different ones which would, in the fullness of time, become separate and mutually incomprehensible languages. I also tried to show how new words would have to be reinvented when old words had been lost. In Dark Eden, having lost the words “sea” and “ocean”, but having retained the word “pool”, John and his followers give the name Worldpool to the large body of water they found on the far side of Snowy Dark. In Mother of Eden, the institution of marriage having been forgotten, new words have had to be invented as something like marriage has re-emerged in both of the main societies. Likewise, since the word “servant” ceased to exist in the relatively egalitarian early days, new words have had to be found to describe people who perform that kind of function in the new near-feudal hierarchies that have emerged.

In relation to society more generally, I just tried to think of the way the dynamic at the end of Dark Eden would lead: an expanding population, enormous new territories, competing leaders and ideas…

4. On a related note, can you describe your process of world-building? How did you go about creating the world of Eden—and even beyond that, imbuing it with a sense of history and tradition? I was struck by how the characters act when they go to Veeklehouse, the same way we might act about seeing a monument today. What’s the process of taking a basic human reaction like that and translating it to a totally foreign environment?

Well of course, that’s an old theme in SF: estrangement, things from the present seen in a new light in the completely different context of the future… And it’s a universal human experience too, isn’t it? Human bodies and minds come and go, but our artifacts may continue for hundreds or thousands of years, as a kind of ghostly reminder that things were not always like this, and won’t always be like this in the future. I live in Cambridge, for instance, in the part of England known as East Anglia and every week or so I walk my dogs along the top of a dyke built a millennium and a half ago to protect the Kingdom of the East Angles against invaders from the West. You can’t know the names of the people who built it, or what was going through their minds as they worked. That’s all gone for good. Yet the dyke remains stubbornly there.

My world-building takes as it starting point my thoughts about the world I actually find myself in and the dynamic that led it to be that way. One thing I try to avoid is going for continual novelty. I don’t want to overload my world with wonders. Of course, I take all kinds of liberties, and yet I want my worlds to feel like worlds and not like theme parks.

5. You’ve written before on the distinctions between literary fiction and science fiction, or “genre fiction” as a whole—including a piece last year for The Atlantic. Why do you think it’s so important to debunk these stereotypes?

Well, my motive is basically selfish. I don’t want people thinking that my stuff is ‘just science fiction’ and therefore not worth taking seriously. I can’t judge the merits of my own work, but I do know it deals with the same range of issues and concerns as any other branch of fiction, and I’d like that to be recognized.

As I’ve said many times before, all fiction involves making stuff up –making up characters, making up situations– in order to be able to explore aspects of life that might otherwise be impossible to reach. (After all, imagination is needed just to put yourself into the head of a person other than yourself.) Science fiction’s one defining feature is that, as well as inventing characters and situations, it also invents worlds that are in some way different from the one we actually know. It’s just another strategy that can used to generate stories, one among many, and I refuse to believe that the mere presence or otherwise of this strategy is reliable indicator of the quality or seriousness of a book. SF can be brilliant, good, bad and terrible, but then so can love stories, or war stories, or stories set in the past…

*More extended thoughts on this theme can be found here in a post I called ‘An unsung Einstein’.

A climate of hope

Nick Brooks drew my attention to this article about the three way relationship between science, art and imagination when it comes to our response to climate change. My thought, as someone who plans to write a novel about climate change (I have written a few short stories about it, including Rat Island, which you can read here) is that the difficult three-way link to pull off is between (a) depicting just how bad the future could be if climate change takes hold (b) nevertheless encouraging hope rather than resignation (a lot of people are simply resigned to climate change, much as they are resigned to their own deaths) (c) managing to do both these while actually being an engaging story.

Over the last few weeks, I’ve actually heard quite a few things that have made me feel encouraged about the possibilities for the future. The Swansea tidal barrage has moved a step nearer being a reality (harnessing a moon-powered energy source that that has the potential to generate a good deal of the world’s electricity). A new kind of aluminium battery, durable and capable of being charged very quickly, has been developed (electricity needs to be more storable and more portable if we are going to move away from fossil fuels for power generation and transport). A new way has been developed of producing hydrogen in a carbon-neutral way from plant waste (hydrogen being another potential clean and portable power source).

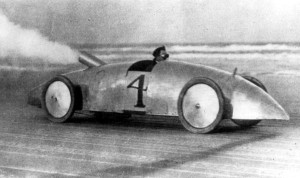

It’s very easy to pick holes in these kinds of developments as solutions to our problems. They can be dismissed as tokenistic or impractical gestures in the face of the scale of the task to be accomplished, and of course many of them will prove to be blind alleys, like steam cars or digital music cassettes. But blind alleys are inevitable in any dynamic evolutionary process. It seems to me that what we have in front of us are the early prototypes of technologies that, when developed and linked up together, could take us into a post-carbon economy. Are the technical challenges really so much greater than those involved in developing the modern car from its primitive forebears, or the modern airliner from the Wright brothers’ ramshackle flying machine?

I’ve no idea how to make these hopeful developments into interesting fiction, or how to combine them with dire warnings about what will happen if we don’t puruse them, so I’ll just lay them out right here.

I guess technology and fiction just don’t necessarily mix. There’s plenty of fiction about space travel, because it can be used to create extreme and exciting scenarios, but how much interesting fiction has been written about communication satellites, the one application of space technology which most of us actually use?