A pleasant spin-off of my recent interest in drawing has been a certain heightened appreciation of the visual world. I find myself noticing things more, asking myself what the essence is of a particular scene, and how a person might go about capturing something of that essence on paper. This April I’ve been taken a special delight in the brightness and colour of Spring, and the intricate three-dimensional patterns of light and space made by new leaves and blossom on the branches of trees. No idea how to draw it really – impressionist smudges capture the colour and light, but can only hint at the spatial complexity – but just thinking about how it might be done makes me feel more part of it.

Serendipitous that at this point, I should take it into my head that I want to read more J.G.Ballard, and specifically The Crystal World:

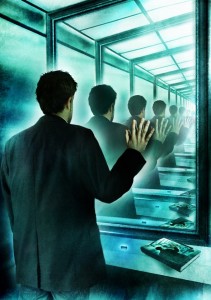

The long arc of trees hanging over the water seemed to drip and glitter with myriads of prisms, the trunks and branches sheathed by bars of yellow and carmine light that bled away across the surface of the water….

Then the coruscation subsided, and the images of the individual trees reappeared , each sheathed in its armour of light, foliage glowing as if loaded with deliquescing jewels…

When Ballard imagines a forest where trees, birds, insects, crocodiles, people are slowly being encased in brilliant coloured crystals that pour out light, he’s describing a sensual delight that’s not so very different from what I am enjoying about the Spring. After all leaves and flowers – complex but endlessly repeated forms, built according to a hidden underlying algorithm – are not really such very different things from crystals.

Ballard referred to surrealists such as Max Ernst among the influences that shaped his work, and he is surely an exceptionally painterly writer, not only because of the attention he gives to visual effects, but also because he is more interested in spectacle and mood than he is in plot. Things happen in his books, but the events are pretty incidental to the evocation of his imagined world, and, insofar as there is movement, it is a movement inwards, a movement towards deeper engagement with what is there from the early pages of the book. Indeed the book itself seems to be about the allure of stasis. The crystals themselves are a product of the leaching away of time.

His is a strange kind of Spring, a Spring that runs joyfully, not towards summer, but towards a kind of shining death.