I was very pleased to be asked to take part in the ‘writer’s rebel’ event last night as part of the Extinction Rebellion protest going on in London. The request was that I do a short reading of my own choice, as one of a number of writers doing the same. Having agonised all week about what to read, I ended up sitting down and writing the following a few hours before the event:

Continue reading “Telling the story of us and nature”Category: Story-telling

Haunted by the Future

I’ve just returned from Novacon 48 in Nottingham. I’m very grateful to the organisers and members for making me so welcome. The following is the text of my guest of honour speech. (I am not a literary historian obviously, so this should be read as the impressionistic ramblings of a writer rather than as the authoritative statement of a specialist.) Continue reading “Haunted by the Future”

Tintoretto

My wife Maggie and I recently spent a few days in Venice. Extraordinary place. It’s has been going round in my head ever since, even in my dreams, like some kind of mystery my brain is trying to solve.

But leaving all the rest of it to the side, here is just one thing we saw there which in itself keeps going round in my head. It’s in the church of San Giorgio Maggiore, on the island of the same name (which you can see across the water if you stand outside the front of the Doge’s Palace) and is a painting of the Last Supper by the Venetian Renaissance artist, Tintoretto.

The original is getting on for six metres wide, so you need to make this picture as big as as your screen can make it if you are to get any sense of it. The thing that struck me at once, not even knowing yet who the artist was (I am no art buff), was the drama and almost eerie immediacy achieved by the arrangement of the figures and by the sharp contrasts between light and shadow. I suppose by far the most well-known picture of the Last Supper is the famous mural by Da Vinci, which is at least as dramatic as this one in terms of what is going on between the characters, but nevertheless seems to me (on the basis of reproductions) to be much further removed from the viewer, much cooler and more static.

The original is getting on for six metres wide, so you need to make this picture as big as as your screen can make it if you are to get any sense of it. The thing that struck me at once, not even knowing yet who the artist was (I am no art buff), was the drama and almost eerie immediacy achieved by the arrangement of the figures and by the sharp contrasts between light and shadow. I suppose by far the most well-known picture of the Last Supper is the famous mural by Da Vinci, which is at least as dramatic as this one in terms of what is going on between the characters, but nevertheless seems to me (on the basis of reproductions) to be much further removed from the viewer, much cooler and more static.

What I get from this painting is a powerful sense of what a mysterious, explosive, dynamic thing a moment is. Everyone in this picture is present at the same point in time, but no two of them have the same sense of what is going on. A couple of disciples towards the left of the picture, for instance, seem to be involved in a conversation of their own that may not even be connected with the famous event unfolding in the middle of the table (an event to be re-enacted over and over again for the next two millenia, including on the altar immediately below where this picture is hung!) The disciple immediately to Jesus’ left seems withdrawn into his own throughts as he watches, perhaps to avoid having to engage with Judas sitting opposite him. Judas, as jealous people passive-aggressively do when trying to undermine someone else’s big occasion, seems to be trying to draw into conversation the disciple being given bread by Jesus. The waiters are getting on with their various jobs: at the near end of the table one of them is asking one of the disciples whether he wants anything else and the disciple is very clearly indicating with both hands: ‘Not now. Something important is happening.’ The semi-transparent angels meanwhile swirl above the scene, drawn in by what (within the terms of this story, obviously) they already know is an event of cosmic significance. Everyone is experiencing this moment in a different way, so that it will explode outwards into the future in many different directions, but, in this instant, they are all in one room, and the same light falls on all of them.

Venice is full of huge Tintorettos. There are lots of them in the Doge’s palace (including some incredibly detailed and energetic battle scenes, which I admired but was not particularly moved by). And the Scuola Grande di San Rocco has two whole floors of them. Most of these didn’t do much for me, I have to say, but they build up to a gigantic, twelve metre-wide Crucifixion in a side room on the top floor which rivals, and perhaps surpasses, the Last Supper for sheer energy. (Again: you need to make this image as big as you can to get any sense of it: it’s packed with detail.) As with the Supper, everyone is seeing different things and many are completely missing the famous drama going on immediately above their heads, but it is a single moment nevertheless, and the whole thing blasts out at you like an exploding bomb.

Dreams, stories, science

In its efforts to be truly scientific, the academic discipline of psychology (which I once studied) relies very heavily on the controlled experiment. There are good reasons for this. As with randomised drug trials, it’s a way (among other things) of elimating the biases, preconceptions and prejudices which inevitably creep in with a more subjective approach. But I wish that psychologists (and indeed scientists more generally) would acknowledge that the methodological self-discipline they impose on themselves does mean that many important and even fundamental questions are simply left outside of their purview. Often, I’ve found, that, rather than admit that their approach has limitations, scientists will simply deny the validity of questions they can’t answer.

For instance, when the idea of the Big Bang was first popularised, the obvious layman’s questions (So what made the Big Bang happen? What was there before the Big Bang?’) were often dismissed as meaningless on the basis that, since there was no time at all until the Big Bang, there was no such thing as ‘before’ it. This drew a sort of figleaf over the fact that the ‘Big Bang Theory’, supposedly a theory about the origin of the universe, in fact completely sidestepped the real questions about the origin of the universe that occur even to very small children: ‘Why is there anything here at all? Where does it come from? How can something emerge from nothing?’

You might say that these questions are simply unanswerable: any explanation would involve postulating some previously existing thing, whose existence would then in itself require explanation. But that doesn’t alter the fact that they are valid questions. Their very unanswerability is, I would say, a profoundly important aspect of the human condition which ought to occasion some humility about the limitations of scientific understanding. Frontiers may be pushed back, but at the core of everything there is always mystery. To deny that, is to deny our own experience.

* * *

Incidentally cosmologists are talking these days about the time before the Big Bang. It seems that, now that there are interesting ideas to explore about the multiverse and bubble universes, the question is no longer meaningless!

* * *

One phenomenon which is extremely resistant to the experimental method is dreaming, since our dreams are invisible to anyone but ourselves and our dreaming selves are never in a position to make notes or measurements (or at any rate, not notes or measurements that will still exist when we wake.) And I’ve come across experimental psychologists being very dismissive about the importance of dreams.

Again, it seems to me, this is an instance of being reluctant to own up to limitations: ‘We are the experts, we don’t know how to answer these questions, so therefore they can’t be important questions.’ Not really ‘scientific’ behaviour, so much the behaviour of a jealous priesthood. After all, if we only took seriously the things and processes whose existence could be demontrated by rigorous experiment, we’d have to jettison most of the contents of our lives, and surrender judgements that we’re perfectly capable of making to professionals to make for us on the basis of a much narrower range of data than we ourselves would naturally deploy.

* * *

I once went to a doctor asking for help managing some symptoms which I knew were the result of anxiety. (The cause of it was no mystery: there was a very big thing I was worrying about). He had me fill in a multiple choice questionnaire, totted up the scores and informed me that I was suffering from anxiety.

* * *

But back to dreams. You only have to consider you own dreams to see the subtlety and complexity of what is going on in them. To give one example: recently both we and our neighbours had building work going on at the same time in our adjoining terraced houses. In the case of the neighbours, this work was so extensive that they had to move out completely for the duration. During this period I had a dream that our builders had accidentally knocked a whole through our shared wall, so that I could see right through into their living room. In my dream, my neighbour Simon came to have a look at the building work, and I greeted him through the hole in the wall, expecting him to be as amused as I was by this tempororary problem. In fact, though, he was angry. It was unacceptable, he said, that our builders should broach their boundary in this way.

Leaving the content of this dream aside (and I haven’t yet extracted any deep meaning from it, although it reminds me of a thing that sometimes happens in conversations when you assume a level of intimacy that the other person is relucant to cede), what strikes me here is what such dreams reveal about the process. In my dream, I expected a certain response from Simon and was surprised when I didn’t get it. Instead I got another response that I didn’t anticipate, but which was also psychologically plausible, and which had been generated for me by another part of me, separate to the part of me that, in my dream, I identified as ‘me.’

One part of my mind, in other words, was generating, not just random thoughts and images, not just random firings of neurons, but a world and characters, as in a story, with which another part of my mind, the story’s protagonist, could interact as if they were real places and people. That’s a fairly complex thing going on there.

And, what’s more, that same ‘other’ part of me -the part that, in my dreams, presents itself not as me but as the world- doesn’t just generate a setting and characters, but also symbols and metaphors. For instance, I once dreamed I saw a blind man begging in the street, completely unaware that right behind him was a broken cash machine pouring out bank notes. Whatever part of me it is that generates the dream world and invents plausible motives for its characters, had here (as on many other occasions) constructed a fairly decent metaphor, in this case for someone who is very unhappy but failing to recognise the opportunites available: my own situation at the time, as I realised when I woke up.

This is not random firings of neurons! This is intelligent story-telling. It shows how dreams include the same basic elements as stories told in waking life, even though we are supposedly ‘unconscious’ when we construct them.

But then, at its core, all story telling is unconscious: you reach into yourself for something and, if you’re lucky, eventually something pops up from…well… somewhere. Another of those unanswerable questions about how something emerges from nothing.

* * *

It seems to me likely that one of the functions served by dreams, as by other kinds of story, is to provide a kind of virtual reality studio in which we can explore or extend or consolidate our experience. (I doubt, incidentally, whether this theory could be demonstrated or refuted by controlled experiments, but supposing it couldn’t be, that actually has no bearing on whether it’s true, only on whether it’s amenable to the scientific method.)

And dreams aren’t even confined to humans. Anyone familiar with dogs knows that that they can be seen running, or barking, or whining in distress in their sleep. Story-telling seems to be hardwired into us, running so deep that it predates the evolution of human beings.

What is the content of animals’ dreams? What does a squirrel dream of? How about a lizard, or a fish? Impossible to answer, but still perfectly reasonable questions.

America City: some background

America City began as a short story called ‘Destiny’. The story itself was never published, its basic flaw being, I realised, that it wasn’t really a short story at all, but an idea for a novel. I’ve just checked and, to my suprise, I find that I wrote it as long ago as summer 2012. Holly Peacock wasn’t in the story, but the basic set-up of America City was there and so was President Slaymaker.

***

Originally, I was going to write this book after completing Mother of Eden. I started work on the novel in 2015, under the working title of Slaymaker, but in the end I decided I wanted to complete my Eden trilogy first, so I set Slaymaker aside to write Daughter of Eden.

The fact that the novel that became America City was originally going to be my next project after Mother of Eden is I think visible in the book. For instance, the relationship between Holly and Slaymaker is a little like the relationship in Mother of Eden between Starlight and Greenstone’s father, Firehand: an ambitious, restless, rootless young woman from a community which values gentleness and fairness, is fascinated by, and feels an unexpected affinity with, a powerful, charismatic and ruthless man a generation older than her, who doesn’t value those things very much at all. (Firehand dies quite early in Mother, so I didn’t get a chance to develop the relationship very much there.)

In both books, too, the ambitious young woman sets out to sell a political idea, and the idea has unintended consequences, as political ideas always do. Both books also make some use of interspersed scenes from the viewpoint of peripheral characters to show the impact of what the major players are doing.

But then again, Mother is set in a sort of bronze age society on a planet with luminous trees and no sun, while America City is set in 22nd century America. And Holly helps Slaymaker, while Starlight sets herself against what Firehand believed in.

***

When I settled down again to write America City in 2016, and through into the beginning of 2017, it was against a new backdrop of real political events: first the Brexit vote in the summer of 2016, and then the rise of Donald Trump. Obviously the book is deeply influenced by my thoughts about why and how these things happened and what I felt I was learning about how politics work.

I felt very challenged by the fact that the 2016 Presidential election was going on as I wrote the book. Here I was, writing about an American politician winning an election by appealing to the tribal instincts of voters, and meanwhile in real life…

In fact, in some respects what was happening in reality was stranger than what was happening in my book. I’m biased of course, but if I compare Slaymaker and Trump, it’s Trump who seems more like a made-up character. So there was a while there when I felt like the real world was overtaking me on the inside lane.

***

I got the name Slaymaker from an administrator at the school of social work at the University of East Anglia, where I was working when I first came up with the idea. Her name is Eve Slaymaker. Names are important. I built the whole character around this amazing surname.

There was another administrator there at the time called Hollie Peacock, and I borrowed her name as well.

***

I don’t often sit down and draw things for a book, but I did design this flag. Holly comes up with it, some way into the book, while passing the time on a flight to Washington, DC.

Words I don’t like #2

There are some words that I think of as typical creative writing words and have never liked. Words that, to me, say, ‘Hey look at me, I’m writing!’ I’ve never liked the word ‘heft’, for instance, as in ‘he felt the heft of it in his hand.’ It means ‘weight’ doesn’t it? Why not just say ‘weight’? No one says ‘heft’ in ordinary speech.

Another one, very unfairly, is ‘grin’, used as a more interesting alternative to ‘smile’. A perfectly ordinary word, I know, and I do choose it occasionally if I find I’ve used ‘smile’ too often, but I really don’t like it and put ‘smile’ wherever possible. ‘Grin’ feels to me, for some reason, like one of those words you fall back on in desperation when you’re trying to bring alive a character on the page who doesn’t even feel alive in your head.

What SF is good for

There is a lovely review of Mother of Eden here. The reviewer, Kevin Elliot, writes ‘”Mother of Eden” is a prime example of how science fiction can handle issues which might pose problems for other genres.’

Well, I’m not the one to say whether Mother of Eden is a prime example of that or not, but I completely agree with him that science fiction is the ideal medium for exploring certain kinds of issue. As I have said elsewhere, science fiction differs from conventional realist fiction in that, while the latter holds the world constant but makes up characters and situations, science fiction makes up the world as well. This means that, while realist fiction is rich in potential for thought experiments about human psychology and human relationships, science fiction offers additional options for thought experiments about society, social structures and social change. The Eden books, for better or worse, are one such experiment.

The realist author takes the existing world (present or past) as given, in other words, but engages in the game of ‘what if’ with characters and their interactions, while SF writers can also engage in ‘what if’ games in relation to the world as a whole. In the case of Eden, I asked myself, ‘what if society evolved all over again from two individuals.’

I’m talking about potential here. Not all science fiction carries out such experiments – the SF pack of playing cards can be used for many different games – and, of course, when it does, it doesn’t necessarily do it well. But this is true also of the realist pack of cards.

Long and cut, or short and add?

I’ll be at Worldcon 75 in Helsinki next week, and I’ve been asked to take part in a panel on ‘Write Long and Cut, or Write Short and Add? (Is it better to write as much as possible and then edit out, or vice versa?)’. If you’re at the con, I hope I’ll see you there! In the meantime, here are a few thoughts:

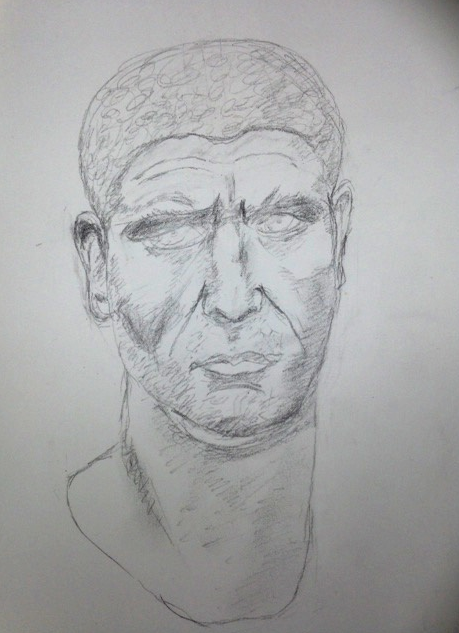

I’ve been doing a bit of drawing lately (one of my recent efforts is below) and one of the things I’ve learnt about that is that you need to be careful to get the basics right before you commit too much to the detail. If you are drawing a face for example, no amount of detail will make the picture look like its subject if the overall shape is wrong. The temptation is to get too engrossed in, say, the shadows around the eyes, only to realise later on that the eyes are too close together, and that at least one of them will need to be rubbed out completely and drawn all over again.

(Roman Emperor, Philip the Arab, drawn at Museum of Classical Archaeology, Cambridge)

(Roman Emperor, Philip the Arab, drawn at Museum of Classical Archaeology, Cambridge)

When writing fiction, there is a similar danger of over-committing to detail at too early a stage. This can result in beautifully crafted scenes which turn out not to fit in, but which you are reluctant to cut because you like them and have committed a lot of time to them: a lot more time can be wasted trying to make the book fit the scene rather than vice versa.

A big difference between drawing from life and writing fiction, though, is that there is no external object to act as a guide: you are not trying to reproduce something in front of you, but rather you are tapping into your knowledge, experience, and subconscious to create a new object that didn’t previously exist. Quite often, the overall shape may actually emerge out of details.

My novel Daughter of Eden, for instance, only came alive for me when I decided to tell the whole thing from the point of view of Angie Redlantern, and for that to happen, I first needed to bring Angie alive for myself by working over scenes told in her voice. Similarly, early drafts of The Holy Machine felt to me they were missing a certain something until I worked out how to write the opening pages. In both cases it was the detail of the voice, and how that voice described its world, that were the key to the entire book. I could have drafted out all the plot outlines I liked, but without knowing how the story was to be told, they wouldn’t have come to anything.

So it is a matter of writing something that vaguely resembles the story that I want to write, or the beginning of that story, and then working and reworking the material until it starts to feel lively. I always start a writing day by revising what I wrote on the previous day, and not infrequently I will go right back to the beginning and revise everything I’ve written so far before carrying on. It’s slow, but it seems to be necessary in order to dig myself down into the story.

As to whether to ‘write long and cut, or write short and add’ I don’t have a straightforward answer. What I’ve noticed is that, as a piece of writing develops, my sense of the centre of gravity of the piece gradually changes and I start to notice what I think of as expansion points and contraction points. In early drafts of the first half of Daughter of Eden, the story was told from multiple viewpoints like the other Eden books and Angie was simply one of several main characters. As I worked and reworked it, I decided Angie was to be at the centre of it, and that all the foregrounded characters were going to be women (Angie, Mary, Trueheart, Starlight and Gaia), while the stereotypically ‘male’ story of war and fighting would be pushed some way back into the mix.

So expansion points are places in the text which seemed of relatively minor importance to start with but are now more important, perhaps to the point where they now feel like the story. In some cases, material which was little more than a connector between two scenes, can turn out to be more important than the scenes themselves. One set of expansion points in Daughter of Eden concerned the Davidfolk’s rituals around circles and the idea of homecoming. That stuff was just a detail at first, one of those things you put in to make a scene a bit more concrete, but it became absolutely crucial to the overall shape of the book, and so I expanded and developed all that, not only by including more detail (the circles, the song, the dots on the foreheads of guards…), but by incorporating those ideas and beliefs into Angie’s thinking.

Contraction points, on the other hand, are places in the text whose importance, or necessity, has diminished over time, so that they need cutting back, or cutting out entirely. In the case of Daughter of Eden this included scenes seen from the viewpoint of male characters, some of which I cut altogether, while others were shortened and retold as observed by Angie, or reconstructed by Angie thirdhand from stories told by others, or relayed by Angie from scenes that Starlight participated in and told her about.

So I suppose my conclusion from all this is, write what you can, and be prepared both to expand and cut.

Writing Daughter of Eden

It seems to be a pattern with me that I faff around with a novel for several months, struggling to find my way into it. And then suddenly something will click, and the novel kind of writes itself. The faffing generally involves a lot of pacing around, eating stuff from the fridge, frittering time on the internet, and spending whole days writing stuff that I know in the evening I won’t be keeping. But I haven’t yet found a reliable way of short-circuiting it.

The turning point for Daughter of Eden was when I decided to abandon the alternating narrator approach used in the other two Eden books, and have one character tell the whole story, relying on hearsay for events she wasn’t present at. The sole narrator, and main protagonist is Angie Redlantern, who appeared at the beginning of Mother of Eden as Starlight Brooking’s best friend. Daughter of Eden centres on Angie’s own adventures after the departure of Starlight.

Once I’d made my mind up to settle down behind Angie’s eyes, the story really started to flow. Angie is a very different kind of protagonist from John Redlantern in Dark Eden, or Starlight in Mother of Eden, and I enjoyed seeing Eden from her perspective. She is a much quieter, more unassuming, gentler figure, her confidence set back by growing up with what people in her part of Eden call a ‘batface’ (i.e. cleft palate/harelip). At the beginning of the book she is living a very humble life: a ‘low person’ , as the Davidfolk call it, right down at the bottom of the pecking order. The big things happen to other people.

But suddenly, she finds herself dealing with huge, cataclysmic events: more cataclysmic than anything in the other two books. I enjoyed watching her grow, while human society on Eden turned itself inside out all around her.

Mother of Eden Q & A

Here’s a short Q & A that the US publishers (Broadway) did with me for Mother of Eden:

1. The protagonist of Mother of Eden is a headstrong, determined young woman named Starlight Brooking, who brings about huge changes in society around her throughout the course of the novel, ending up as a truly revolutionary figure. Did you make a conscious decision to have a female protagonist? What is the role of female characters in science fiction in general, and has that changed over the years?

I guess as a writer, one tends to default to viewpoint characters who are a bit like yourself. Well, I know that’s true of me anyway, and so I make a conscious effort to try and develop main characters who are different. John Redlantern, in Dark Eden, while male, was unlike me in that he is very much a doer: someone who must be constantly on the go in order to feel alive. (This really isn’t me at all! I’m very good at doing nothing!)

Given that the protagonists of all my novels, and the majority of my short stories, had been men, I decided that it was about time I wrote a novel with a female main protagonist. In fact Starlight is female and a doer. (She’s also less than half my age, but this is common for my characters. I don’t seem to have done with that time of life!)

I like Starlight as a character. Others will have to judge of course, but, apart from that first little conscious effort of choosing a female protagonist, I didn’t find it hard to write from her perspective. Then again, I have three sisters (no brothers), two daughters, a mother, a wife, women friends, and I have worked most of life in a profession which is 85% women. If I’ve being paying attention at all, I really ought to be able to describe things from a women’s perspective!

As the book developed, it became increasingly about women too. As in Dark Eden, the story is told by a number of different people and, at one point I thought of having only women as viewpoint characters. In the end, although most of the viewpoint characters are women (Starlight, Glitterfish, Julie, Quietstream, Lucy…), I did include two men: the gentle Greenstone, and the brutal Snowleopard.

I am sure that most of the science fiction I read growing up in the seventies was (a) written by men, and (b) had men as main characters, with women mainly present as objects of love and desire. I think SF has moved on from that, thank goodness. However it does strike me that we are still better in SF at writing about tough male and female protagonists acting in stereotypically “masculine” ways, than we are at writing about people (men or women), who are gentle and nurturing in stereotypically “feminine” ways. I think that’s something to think about. After all, we need nurses and teachers at least as much as we need soldiers and atomic scientists, and I would say a good deal more so.*

2. Mother of Eden has so much to say, as Dark Eden did, about how civilizations develop and the sacrifices we make in the process. Did you start with certain issues that you wanted to address, or did those come naturally as you wrote the novel?

Well, both. I think the content of this book flowed naturally from Dark Eden, and some basic themes were certainly there in my mind from the beginning. But new themes and ideas emerged as I went along.

In Dark Eden, I showed a society that was becoming increasingly dominated by men, and increasingly controlled by violence. I knew from the beginning I wanted to think about how that developed. In Mother of Eden, the followers of David and the followers of John have created two hierarchical, militarized and male-dominated societies (a description which, of course, would still fit most of the societies on Earth today). However in both societies, there persists a folk memory of the time when the whole human community of Eden was a single family in which the central figure was a woman. (I think this is also true for most of us on Earth today: most of us grew up in an environment in which a woman was the dominant figure, our primary source of nourishment and comfort and safety, insofar as we had these things at all). Even in these male-dominated societies, it seemed to me, women still had immense power, and men, afraid of this power, had tried to channel and control it in various ways to make it serve their purposes. Gela’s ring, which Starlight puts on her finger, became a focal point for a lot of my thinking about this.

Something that emerged as a theme as I went along was power more generally. Not just men’s power and women’s power, but power itself: what it is, where it comes from, what you have to do to get it.

Another theme, that was of course present in Dark Eden also, is our relationship with the past. Now of course, the story of Dark Eden is itself the past, and we have two different societies whose enmity is based on their different takes on the meaning of those events, much as (for example) the enmity between Sunni and Shi’ite Muslims in the world today is a continuation of a quarrel that goes back to the eighth century.

As to the sacrifices we make in order to progress, yes this remains a big theme in this book. I am struck by the idea that every human society is a kind of compromise. To get one thing, we have to give up another. There is always a price for everything, it seems to me. This means that if you want easy answers, or comforting messages about how one day everything will all be wonderful, then I’m not the person to come to! I guess if I had an easy answer, I wouldn’t be writing novels!

3. Mother of Eden takes place 200 years after the events of Dark Eden. How did you decide which changes would have taken place in that time? How has the language changed as the inhabitants of Eden have lived there over the decades?

The decisions you make when writing a book of this kind are always a compromise between realism and what works for the story. I did not make major additional changes to the language, over and above those made in Dark Eden, because I didn’t want to make things too difficult for the reader, but I tried to give some sense of the fact that geographical dispersal has meant that people in Eden no longer speak a single dialect but several different ones which would, in the fullness of time, become separate and mutually incomprehensible languages. I also tried to show how new words would have to be reinvented when old words had been lost. In Dark Eden, having lost the words “sea” and “ocean”, but having retained the word “pool”, John and his followers give the name Worldpool to the large body of water they found on the far side of Snowy Dark. In Mother of Eden, the institution of marriage having been forgotten, new words have had to be invented as something like marriage has re-emerged in both of the main societies. Likewise, since the word “servant” ceased to exist in the relatively egalitarian early days, new words have had to be found to describe people who perform that kind of function in the new near-feudal hierarchies that have emerged.

In relation to society more generally, I just tried to think of the way the dynamic at the end of Dark Eden would lead: an expanding population, enormous new territories, competing leaders and ideas…

4. On a related note, can you describe your process of world-building? How did you go about creating the world of Eden—and even beyond that, imbuing it with a sense of history and tradition? I was struck by how the characters act when they go to Veeklehouse, the same way we might act about seeing a monument today. What’s the process of taking a basic human reaction like that and translating it to a totally foreign environment?

Well of course, that’s an old theme in SF: estrangement, things from the present seen in a new light in the completely different context of the future… And it’s a universal human experience too, isn’t it? Human bodies and minds come and go, but our artifacts may continue for hundreds or thousands of years, as a kind of ghostly reminder that things were not always like this, and won’t always be like this in the future. I live in Cambridge, for instance, in the part of England known as East Anglia and every week or so I walk my dogs along the top of a dyke built a millennium and a half ago to protect the Kingdom of the East Angles against invaders from the West. You can’t know the names of the people who built it, or what was going through their minds as they worked. That’s all gone for good. Yet the dyke remains stubbornly there.

My world-building takes as it starting point my thoughts about the world I actually find myself in and the dynamic that led it to be that way. One thing I try to avoid is going for continual novelty. I don’t want to overload my world with wonders. Of course, I take all kinds of liberties, and yet I want my worlds to feel like worlds and not like theme parks.

5. You’ve written before on the distinctions between literary fiction and science fiction, or “genre fiction” as a whole—including a piece last year for The Atlantic. Why do you think it’s so important to debunk these stereotypes?

Well, my motive is basically selfish. I don’t want people thinking that my stuff is ‘just science fiction’ and therefore not worth taking seriously. I can’t judge the merits of my own work, but I do know it deals with the same range of issues and concerns as any other branch of fiction, and I’d like that to be recognized.

As I’ve said many times before, all fiction involves making stuff up –making up characters, making up situations– in order to be able to explore aspects of life that might otherwise be impossible to reach. (After all, imagination is needed just to put yourself into the head of a person other than yourself.) Science fiction’s one defining feature is that, as well as inventing characters and situations, it also invents worlds that are in some way different from the one we actually know. It’s just another strategy that can used to generate stories, one among many, and I refuse to believe that the mere presence or otherwise of this strategy is reliable indicator of the quality or seriousness of a book. SF can be brilliant, good, bad and terrible, but then so can love stories, or war stories, or stories set in the past…