While on the subject of ads, let me admit that there is a copywriter inside me, crying to be let out. I once whiled away an hour on a train by devising in my mind an entire advertising campaign for McCoy’s crisps, including TV ads, posters and merchandise.

I did actually think about being a copywriter when I was a kid, inspired, as I said before, by The Space Merchants – in spite of (or, to be honest, probably because of) that book being about the dangerous power of advertising. Unfortunately for my advertising career, I did also internalise the book’s political message, and by the time I was old enough to need a job, I didn’t feel able to give over my life to helping giant corporations sell harmful things.

But I think I would have been good at copywriting. It certainly would have been a better fit with my skills than being a social worker, and an excellent training for being a writer, at least in the narrow sense of honing my skill with words, because the best advertising copy has something in common with poetry – it has to be as succinct as possible and make every word count – but with the added twist that, unlike poetry, it has to work even when its readers have barely noticed that it’s there.

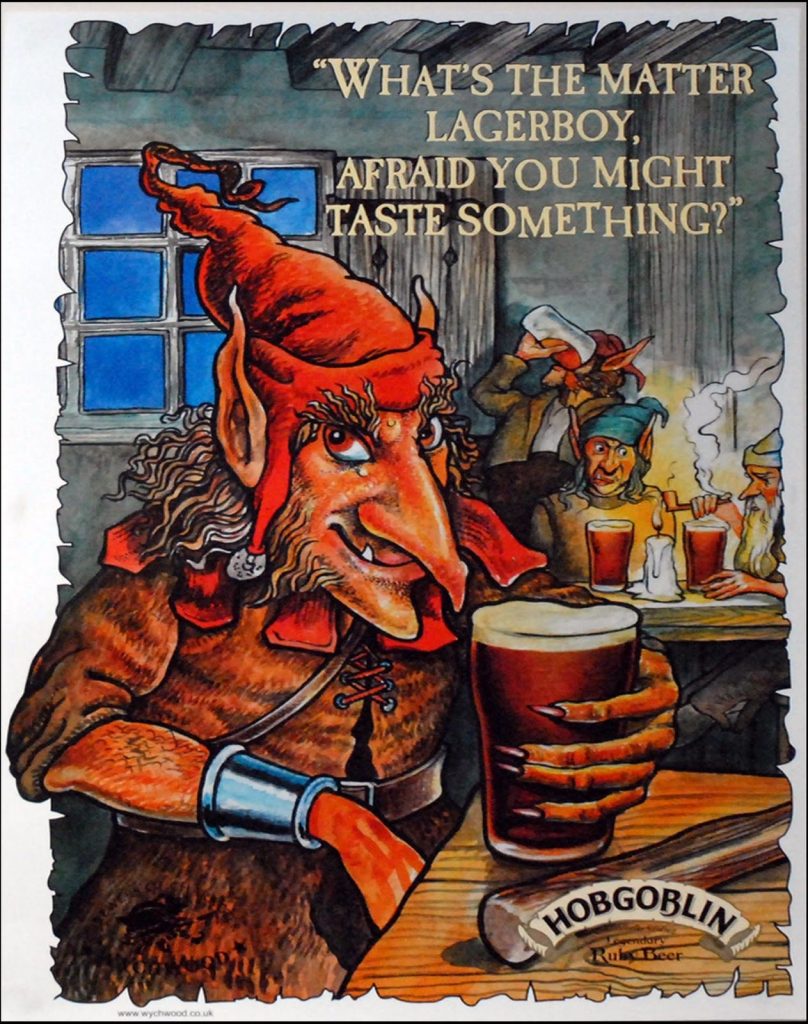

This ad from a while back seems very simple, but is a small masterpiece of compression.

The final sentence – ‘We’ve got sales targets’ – is disarming and funny because it frankly admits the real purpose of the ad, and yet it doesn’t in any way reduce the impact of the sequence set up by the previous sentences and the picture of the drink: summer (hot), thirsty (unpleasant), and Oasis (a cool and refreshing release from heat and thirst – and, speaking of release, isn’t that image quite blatantly orgasmic?)

In fact, far from reducing its overall impact – the ‘sales target’ sentence allows the rest of the ad to slide gently into your consciousness (and, more importantly, into your unconscious), like the smooth coating on a pill, without seeming too bald and shouty.

And notice how ‘You’re thirsty’ is in a larger font. So often when we’re busy, we don’t notice our bodily sensations until something draws them to our attention. (When I was a social worker, I would often notice right at the end of the afternoon that I felt quite light-headed, and realise that I’d forgotten to eat my lunch.) Also, though I don’t really know why this should be, ‘thirsty’ is a particularly powerful word with lots of bite. Much more so than, say, ‘hungry’ or ‘tired’.

Brilliantly effective writing. And all done in eight words – or nine including the bottle. I can’t stand those kinds of drinks as it happens, but it would have worked on me otherwise, no question about it. And, if only it wasn’t for my political scruples, I would have loved to have worked on ads like that.