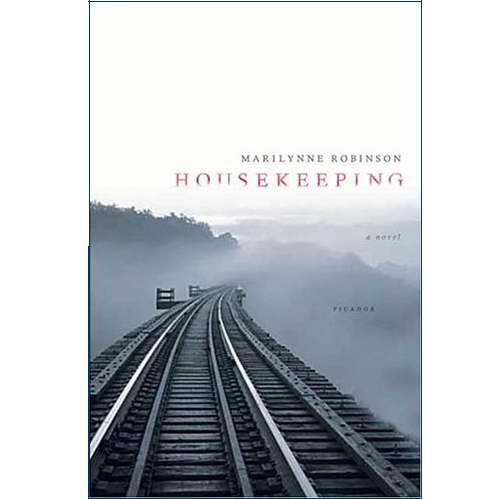

Housekeeping, by Marilynne Robinson (published 2004)..

Housekeeping, by Marilynne Robinson (published 2004)..

Two sisters grow up in a small town in Idaho beside the large lake that claimed the lives of both their grandfather and their mother, and the railway bridge that spans it. Their grandmother looks after them until she too dies, and then two great-aunts who are more accustomed to shabby-genteel life in a hotel room than managing a household with children, and then finally their odd, solitary, distracted aunt Sylvie, who has lived her life as a transient, picking up work here and there, riding in boxcars, gathering odd little yarns from passing acquaintances. The sisters and their aunt live a deeply eccentric life, largely cut off from the rest of the community. One of the sisters (Lucille) eventually breaks free of this, the other (Ruth, who is also the narrator) does not.

An important character in this book is the material world -the lake and its shores, the house, the bridge- which for a lot of the time is Ruth’s (and her aunt’s and her sister’s) main companion. Here, for instance, Ruth and Lucille are out by themselves on the frozen lake. Over on the shore fires are burning in barrels to warm the townsfolk who come down to skate on the ice, but the two sistes, typically, are far out at the extremity of the area that is swept of snow to provide a skating rink :

The town itself seemed a negligible thing from such a distance. Were it not for the clutter on the shore, the flames and the tremulous pillars of heat that stood above the barrels, and of course the skaters who swooped and sailed and made bright, brave sounds, it would have been possible not to notice the town at all. The mountains that stood up behind it were covered with snow and hidden in the white sky, and the lake was sealed and hidden, yet their eclipse had not made the town more prominent. Indeed, where we were we could feel the reach of the lake far behind us, and far beyond us on either side, in a spacious silence that seemed to ring like glass.

Or here is a beach on the lake:

The shore drifted in a long, slow curve, outward to a point, beyond which three step islands of diminishing size continued the sweep of the land toward the depths of the lake, tentatively, like an ellipsis. The point was high and stony, crested with fir trees. At its foot a narrow margin of brown sand abstracted its crude shape into one pure curve of calligraphic delicacy, sweeping, again, toward the lake.

These are empty vistas. Their emptiness is part of their mystery and their allure. But human relationships are evoked with the same elegance and economy. Here is Lucille beginning to pull away from her sister Ruth and from the eccentric isolation of their life with Sylvie. Ruth has gone to fetch a dictionary at Lucille’s request (in order to find out what ‘pinking sheers’ are, Lucille having decided to make herself some decent clothes from a pattern) and, opening up the book, she finds it full of dried flowers, carefully pressed there by their long-dead dead grandfather:

“Let me see that,” Lucille said. She took the book by each end of its spine and shook it. Scores of flowers and petals fell and drifted from between the pages. Lucille kept shaking until nothing more came, and then she handed the dictionary back to me. “Pinking sheers,” she said.

“What will we do with these flowers?”

“Put them in the stove.”

“Why do that?”

“What are they good for?” This was not a real question, of course. Lucille lowered her coppery brows and peered at me boldly, as if to say, It is not crime to harden my heart against pansies that have smothered in darkness for forty years.

A theme that runs through the book is the paradoxical nature of loss, the way that something or someone lost can be a much bigger matter than the actual presence of that something or someone would ever have been. Lucille is fighting this when she hardens her heart against the flowers. And it is her that manages to escape the odd solitary menage she shares with her aunt and sister.

Towards the end of the book, Ruth reflects on how how she and Lucille lived lives dominated by the shadow of their mother’s absence. But…

…if she had simply bought us home again to the high frame apartment building with the scaffolding of stairs, I would not remember her that way. Her eccentricities might have irked and embarassed us when we grew older… We would have laughed together at our strangely solitary childhood, in light of which our failings would seem inevitable, and all our attainments miraculous. Then we would telephone her out of guilt and nostalgia, and laugh bitterly afterward because she asked us nothing, and told us nothing, and fell silent from time to time, and was glad to get off the phone.

Ruth’s degree of insight stretches credulity a little here. One accepts the literariness and poetry of Ruth’s voice as a device, but it is hard to believe that this drifting isolate, looking in at the world from outside, could really acquire any kind of understanding of the bitter, guilty dutifulness of the middle-aged grownup children of a not-very-satisfactory mother.

But never mind. What I got very powerfully from this book -and I keep coming back to it in my mind- is a demonstration of how absence becomes addictive. Look at the photo on the cover. How much more myterious and alluring is the part of the railway track in the distance that is disappearing into the mist, than the part in the foreground you can see perfectly clearly. Dwell too much and too long on absence, and mere presence will never be enough.