I’m taking part in several panels at the World SF Convention in London this August (details here).

Below are some preliminary thoughts for the panel on Philip K. Dick. (Through a Hollywood Adaptation, Darkly: Thursday, August 14th, 18:00 -19:00). The other panellists will be Christi Scarborough, Grania Davis and Malcolm Edwards, and the blurb for the panel is as follows:

Thanks largely to the ever-increasing number of film adaptations of his work, Philip K Dick is one of the small number of genre authors whose names have been commoditised: “Dickian” is now a shorthand for paranoia, shifting realities and unstable identities, or even for the condition of twenty-first century life in general. But to what extent is this cliché precis an accurate reflection of the breadth of Dick’s work? What other themes and preoccupations can we see in his novels and stories? How far does his influence on modern SF really extend — and what rewards does his work offer to new readers today?

No one could deny that paranoia, shifting realities and unstable identities are major themes in Dick’s work, and Dick is indeed sometimes hailed as a kind of uniquely prophetic voice on ‘the condition of twenty-first century life’, a post-modernist ahead of his time. But yes, this is a cliché precis. Not only is there a lot more to Philip Dick than it suggests, but, even as a summary, it is somewhat misleading.

First of all, while Dick’s shifting realities may seem post-modern, Dick wasn’t really a post-modernist at all. Post-modernists emphasise plurality and flux: there isn’t one reality, but many different realities. Dick’s work may superficially seem to conform to this view of the world, but in fact what he depicts again and again are people dealing, not with many different equally valid realities, but rather with falsehoods and illusions which seem real, but are actually fake. Dick’s characters are always searching for authenticity, for reality in the singular. They may never find it, they may fear that it can’t be found, but they never stop looking for it. This isn’t post-modern, it’s positively pre-modern, and the more so in Dick’s later works where he is increasingly drawn to Christian theology, albeit in a particularly dark, scary and Dickian form. (No one ever describes as Dickian the belief that the world is a battleground between the followers of Christ and the servants of darkness – it doesn’t chime so well with a vision of Dick as edgy, contemporary, prescient – but it’s very much part of the vision of his later work.)

Secondly, I think the conventional precis of Dick’s work overemphasises the extent to which his work can be read as a social commentary. I would argue on the one hand that his work operates much more at the psychological level (as opposed to the sociological one), and, on the other, that he is at least as preoccupied with things that he sees as timeless, as he is with the condition of society at a particular point in history. (One of the appeals of writing SF, it’s always seemed to me, is that it does allow one to step outside the parochial concerns of the present moment.) Of course Dick’s work reflects the time it was written in – a time which was simultaneously one of great optimism and one of terrible darkness and violence – but the two deepest roots of his writing, it seems to me, extend outwards on either side of the ‘social’. On one side, many of his preoccupations are very personal ones: for instance the figure of the dead female twin, which appears again and again in his work (Valis, Flow my Tears, Dr Bloodmoney…) comes directly from Dick’s own biography: his own twin sister Jane died in infancy. On the other side it is metaphysical, concerned with the place of the human soul in the universe (which is where Dick’s quirky version of Christian theology comes in). His greatness lies in the way he linked up the personal with the universal.

Here are some recurring themes I’ve noticed in Dick’s work:

A sense of loss.

This, I imagine, had very personal origins for Dick. Parents grieving a dead child are not best placed to welcome a baby into the world, and I would guess his life felt very lonely indeed from the start. (Look at the dark, lonely and guilt-ridden childhood depicted in the brilliant short story ‘I Hope I shall Arrive Soon.’) Dick’s experience wasn’t unique though. A feeling of loss, of absence, of insufficiency, is part of the human condition. Hence the Biblical legend of the Fall. Valis is a particularly terrifying vision of a fallen world, a world in the sway of darkness, but the same vision is to be found in Flow my Tears and Palmer Eldritch among many others. And the figure of the dead twin sister (elevated in Valis to a dead female demiurge), which so clearly comes from Dick’s own biography, is turned into a powerful metaphor for the feeling of loss and absence which we all know.

Even those famous ‘shifting realities’ are also in a way representations of loss. That’s what loss is like. We think something is real and then it is snatched away from us. Ragle Gumm in Time out of Joint (surely the prototype for the film The Truman Show?) imagines the world he’s in is real, but it turns out to be a crude set of stage props, Rick Deckard in Do Androids Dream finds what seems to be a real animal, and then finds the tell-tale battery compartment.

In the story ‘I Hope I Shall Arrive Soon’, we find another take on ‘shifting realities’ and their relationship to loss. The main character Victor Kemmings is starting out on a ten year journey to another planet, during which he is supposed to be in a state of cryogenic suspension. Something has gone wrong. He is still conscious and faces the prospect of spending the next ten years lying all alone in a kind of coffin. Realising that he will go completely mad, the intelligent spaceship tries to ease the situation by feeding him his own memories, but Kemmings’ past is so painful to him that this only makes things worse. Finally the ship hits on the idea of feeding him, over and over, the illusion of arrival. Again and again, Kemmings reaches his destination and disembarks, only for the illusion to unravel and the ship have to run it all over again. It keeps Kemmings sane for ten years, but at a cost. When he really does arrive, he still can’t believe it’s real.

If we have to retreat into illusion to keep ourselves sane, the story suggests, the price we will pay in the long run is that nothing will ever seem quite real. This is very much a psychological explanation for those famous paranoid scenarios – and one consistent with the work of object relations psychologists such as Bowlbly, Klein or Winnicott – as opposed to a sociological, political or cultural one.

The cherished possession

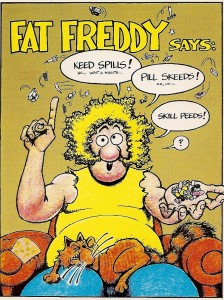

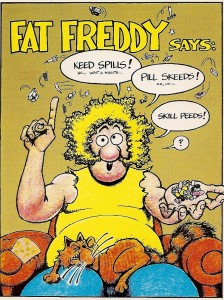

Another figure I have noticed many times in Dick’s work is what I call ‘the cherished possession’. This is some treasured object which has huge significance for the character. In Do Androids Dream, for instance, Deckard longs to possess a real animal. He keeps an electric sheep as an affordable substitute, but what his heart is set on is a real one, and he spends a lot of time hanging around outside pet shops and thumbing through his catalogue. In High Castle, Mr Tagomi possesses a jewel which somehow exists of itself, and not simply as a human projection. In Flow my Tears both the powerful policeman Felix Buckman and his sister-lover Alys are assiduous collectors of objects of many kinds and Buckman secures his sister’s co-operation at one point by making a present to her of a particularly fine postage stamp for her to ‘put it away in your album in your safe forever’. In the short story, ‘I Hope I Shall Arrive Soon’ (about which I once wrote an MA dissertation: hence my particular emphasis!), the cherished object is a poster of ‘Fat Freddy’ from the Furry Freak Brothers comics called ‘Speed Kills’, signed by the artist Don Shelton. (Both the poster and the artist are real, incidentally. The poster in question is below.)

These cherished possessions are, of course, subject to the same anxious doubts as other aspects of Dick’s world. Supposedly real animals may turn out to be electric ones, a supposedly authentic object may turn out to be a fake. In High Castle there is a debate about the authenticity of a cigarette lighter alleged to have belonged to Franklin Roosevelt. Yes, there are letters of authenticity, but how do we know that they themselves aren’t fake? Exactly the same debate takes place about the Gilbert Shelton poster in ‘I Hope I Shall Arrive Soon.’

Hope

One other thing that isn’t so often commented on in Dick’s work is that, however dark the scenario, however terrifying the forces against which they are pitted, the characters themselves are never completely devoid of good humour or hope. ‘I mean, after all,’ says the indefatigable Leo Bulero in Palmer Eldritch, ‘you have to consider we’re only made out of dust… But even considering, I mean it’s a sort of bad beginning, we’re not doing too bad. So I personally have faith that even in this lousy situation we’re faced with we can make it.’

In the poisoned Earth of Do Androids Dream millions of people subscribe to the stoical religion of Mercerism, using devices known as ‘empathy boxes’ to connect themselves to the vision of their prophet, Wilbur Mercer, as he struggles eternally up the slopes of a bare mountain in spite of rocks and stones that are constantly being cast at him. At a certain point in the novel a TV programme exposes this central scene of Mercerism to be a forgery, faked up in a film studio with an actor playing Mercer against a crude painted backdrop (close examination reveals the actual brush-strokes). And yet somehow in spite of this the truth of Mercerism – its utility in enabling people to engage with one another and with their harsh existence – remains undimmed while those who exposed the artifice turn out to be artefacts themselves. (They are androids, famously distinguishable from human beings by their inability to experience empathy).

In suggesting that it is the would-be debunkers, not the Mercerists, who are missing the point, Dick cuts through all the paranoid doubts about reality and authenticity which are such a constant theme of his work, and challenges his own definition of reality (in Valis) as ‘that which when you stop believing in it, it doesn’t go away’. If we are to have a shared reality with other people then this has to be able to include things that are sustained only by belief. After all empathy itself depends on our belief in something that can never actually be proven to be true: that other creatures have feelings which are in some way equivalent to our own.