If you subscribe to a belief, certain thoughts become unthinkable. So, for instance, if you subscribe to a belief in socialism, and you are presented with the various historical examples of socialism failing to deliver, you have to conclude that it just wasn’t done right, or was done in the wrong circumstances, and needs to be tried again, because the conclusion that socialism doesn’t work isn’t available to you. (Feel free to substitute laissez faire capitalism in that example: it is equally applicable). In the same way, if you believe that a loving and omnipotent god created the world, you have somehow to find ways of explaining the existence of (for example) agonising and degrading diseases that are consistent with such a god, because the much simpler explanations available to an atheist aren’t on your list of options.

Belief results in a certain inflexibility, in other words.

But belief is nevertheless essential to life. For one thing, we have to make decisions all the time in situations where there isn’t enough exact information to be certain of what the outcomes will be (this is true of almost all political decisions and all but trivial personal ones), or where the judgement to be made involves values (again true of most political and personal decisions). Without beliefs we’d have nothing to guide us.

The inflexibility of belief, while sometimes a problem, is also the key to its usefulness. It allows us to set or harden things that would otherwise be fluid. In order to be able to think about ourselves as coherent human individuals, and not just a bundle of impulses, we have to ‘keep faith’ with decisions already made. Marriage, for instance, involves keeping faith with the idea that you love someone and belong with them, even through times when you don’t actually feel love and aren’t enjoying being together. In other words you have to believe that what you felt in the past was real, even when it doesn’t seem so now, and you have to believe that you will feel it again. And the same applies to other kinds of commitments: an example in my case would be the writing of a book, which would never get done if I didn’t force myself to keep plugging on through long periods when I felt almost certain that the whole project was worthless, and that I nothing left to say.

Faith, in this sense, is a kind of belief that allows us to tie together the past, the present and the future, even though all we can ever actually directly know is the present. I think of it as a kind of human chain, such as might be used to rescue people from a shipwreck, except that this chain is made up, not of different individuals, but of different iterations of the same individual. For someone prone to self-doubt and mood swings, such as myself, holding hands with your past and future selves can be pretty challenging. (My wife would vouch that I can easily move in a single day between cheerful optimism to existential despair, and sometimes find it hard to give any credence to my former self of only a few hours ago.)

I hate to admit it, but I suppose what I’m talking about now is the kind of belief that’s referred to in a thousand cringy Hollywood movies when one character tells another ‘you’ve got to believe in yourself’ or ‘if only you believe in yourself anything is possible’. Clearly the latter is a lazy cliche: no amount of self-belief will make me (say) a premier league footballer. But it is true that you do need to believe in your ‘self’ in order to be able to achieve anything substantial, because unless you believe in a coherent self that is continuous over time, it is impossible to commit yourself to the work involved.

Your ‘self’ is, in fact, just a particular example of a whole class of entities that are necessary in order to function in society, but which owe their existence to belief. A nation is such an entity. Benedict Anderson famously described a nation as an ‘imagined community’. This is not the same thing as an imaginary community, because an imagined community really does exist. It’s just that it only functions because it is imagined. And imagination in this sense is closely related to belief. Believing in oneself and believing in a nation both entail being able to imagine a connection with a bunch of people you can’t actually see and can’t directly know: in one case these people are your future selves, in the other, compatriots you’ve never met.

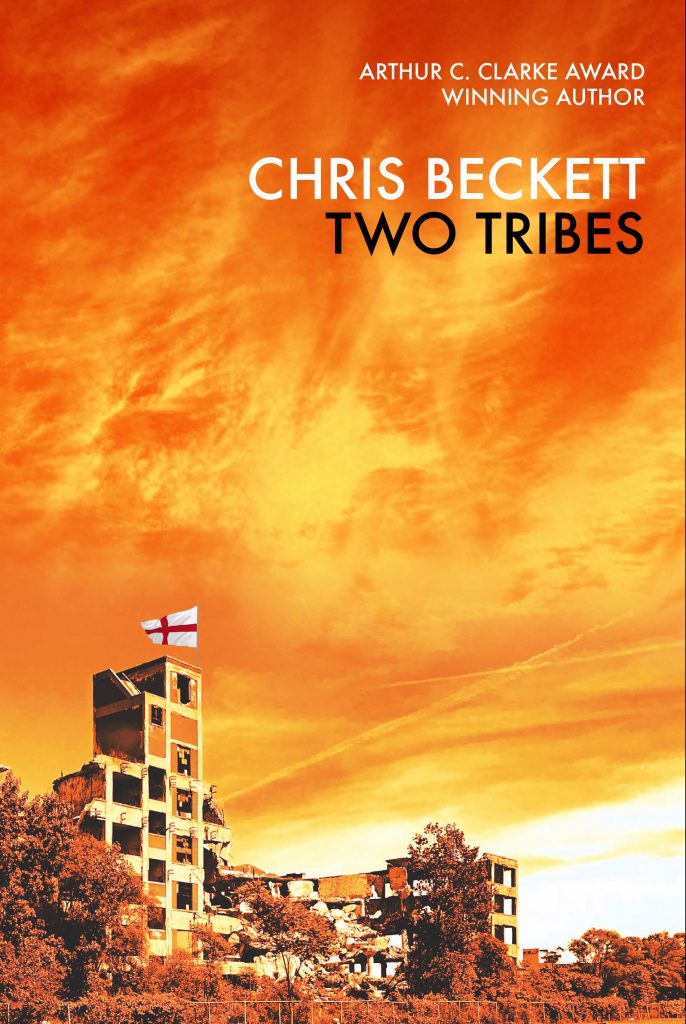

Recent divisions in the UK are characterised by some as a rift between the blind belief of the ignorant and the rational evidence-based thinking of the educated (I’ve seen this thought expressed earlier today on social media). But actually both sides are sustained by beliefs in imagined communities. It’s just unfortunate that they aren’t the same ones. ‘I am a European first and foremost’ is resonant for some, ‘I am English [or British, or Scottish, etc] first and foremost’ is resonant for others. Some, I know, even combine both. For many only one of these statements is real and the other is simply a fabrication. But these are all statements of belief, elements of the stories that we choose to live by, not facts that can be objectively verified.