I’ve just returned from Novacon 48 in Nottingham. I’m very grateful to the organisers and members for making me so welcome. The following is the text of my guest of honour speech. (I am not a literary historian obviously, so this should be read as the impressionistic ramblings of a writer rather than as the authoritative statement of a specialist.) Continue reading “Haunted by the Future”

Category: All posts

Interview with Robin Shantz

New podcast interview here with Robin Shantz aka Bloginhood.

Beneath the World, a Sea

The Mind is Flat by Nick Chater

If I were to describe this book as superficial (which I would) the author should perhaps be pleased, for he sets out specifically to show that the mind contains no hidden depths.

If I were to describe this book as superficial (which I would) the author should perhaps be pleased, for he sets out specifically to show that the mind contains no hidden depths.

Nick Chater starts with visual perception and he shows that we actually see much less than we think we see. This is something that’s struck me before. For example, focus on an object in front of you, a mug for instance, and then, without moving your eyes, notice how little else you can see while you remain looking at the mug. You’ll find that, even in the immediate vicinity of the mug, your visual field is a blur. Apparently if you get someone to read a page of text on a screen, and change all the words except the ones they’re looking at into rows of x’s, they won’t notice the difference! And something I didn’t know until I read this book is that the blurred forms you see at the edge of your field of vision aren’t even in colour. (I tested this myself and it’s true!).

This is all fascinating stuff (and I enjoyed reading about it), but I take issue with the author when he asserts that our impression of seeing the whole world in front of us is an ‘illusion’ (the Grand Illusion as he calls it), and even more so when he calls it ‘fake’ or a ‘hoax’. Our perceptual apparatus isn’t just presenting us with the raw sensory data, that’s true, but that would be pointless, and its job is to assemble fragments into a stable and coherent sense of where we are. But why on earth call the result a hoax? A radar screen shows incoming planes in the vicinity as blips. These are refreshed with each new sweep of the continuously revolving antenna and in fact the antenna is only detecting a few of those planes at any one moment. But does this mean it’s just a hoax or an illusion that makes us think those blips show the positions of all the planes in the vicinity? Of course not. What the screen shows is an approximation perhaps, but that’s not the same thing as an illusion at all, and it’s an accurate enough approximation for air traffic controllers to safely manage incoming planes at busy airports, day in day out, for months and years on end.

Having discussed perception, Chater then goes on to talk about cognition. Just as experiments on perception show that we see much less at any given moment than we might think, so too do experients show that our thoughts are much more circumscribed than we might imagine. In fact, at any one time, we can only pay attention to a very limited number of mental tasks. I can drive and sing. On a clear straight road, I can drive and list prime numbers (I tried it out recently). But I can’t drive, sing, and list prime numbers all at once. In fact, Chater suggests, our sense of a rich mental life with many layers is a hoax, just like the illusion that we can see a rich detailed exterior world. ‘Our thoughts are not shadows of an alternative inner reality to be charted and discovered; they are fictions of our own devising, created moment by moment.’ Even emotions, it seems, are ‘just fiction too.’

But hang on. There is a rich external world out there, that’s not disputed. So, insofar as there’s an illusion going on perceptually, it’s not the existence of that world, it’s the fact that we imagine ourselves to be taking in that world whole and all at once, whereas what we’re really doing is forming a (pretty serviceable) impression of it a little bit at a time. And surely the same is true of our inner life? The fact that I am not thinking lovingly of my children at every moment in time, doesn’t mean that it’s just an illusion that I love my children, any more than the fact that I’m concentrating on my computer screen just now means that there isn’t still a garden through the door to my right.

The funny thing about all this –and Chater does acknowledge it himself- is that, in order to dismiss depth, he has to introduce an incredibly powerful unconscious mechanism. He argues that our sense of having a coherent self is an illusion that is being constructed for us in the moment by this powerful unconscious process, with the the result that, though we imagine that we are drawing on some inner self, in fact ‘we are quite literally making up our minds, one thought at a time’. So, in other words, our sense that our thoughts come from something complicated inside us is an illusion being created for us by… well… something complicated inside us!

He doesn’t have very much to say about how this mechanism works -the book concludes with a slightly hand-wavy paeon to human imagination- but clearly it must draw on memories of previous experiences . It follows, surely, that this very powerful and complex unconscious process is actually not just making up our minds for us out of the blue but is rather surveying the relevant parts of our vast existing store of knowledge and experience, much in the same way as when we are walking down a road, our perceptual apparatus surveys the relevant parts of the external world.

Et voilà! Depth is back again with a different name. (Chater himself speaks of ‘an ever-richer web of connections across our mental surface’.) It is a vast and complex inner landscape, but one which (as few of us will be surprised to learn), we cannot see in its entirety all at once.

* * *

One thing that strikes me about this book is that, while it describes as an ‘illusion’ or a ‘fake’, impressions of the world assembled by the sensory system from fragments, it is happy to present a version of the world that is also assembled from fragments, in this case controlled psychology experiments. Not only do these experiments (fascinating as some of them are) constitute discrete and pretty miniscule glimpses into the operations of the human mind, but the interpretations placed on them seem extremely questionable.

For instance, he describes a series of experiments in which people make different choices depending on how the same options are presented to them, and suggests that this demonstrates that ‘preformed beliefs, desires, motives, attitudes to risk lurking in our hidden inner depths are a fiction’. There’s ‘no point wondering,’ he says, ‘which way of asking the question… will tell us what people really want… not because our mental motives, desires and preferences are impenetrable, but because they don’t exist.’ This is an extraordinary bold claim to make on the basis of a few experiments in which people are offered some rather artificial choices. And it seems to me that a much simpler explanation of the findings of these experiments is that people have competing wants (for example, a desire to make money, versus a desire to avoid risk), and that, depending on how questions are put to them, different wants come to the fore.

I want to keep fit, I also want to eat ice cream. In my experience this can lead to decisions which contradict one another.

* * *

So much of what we think we know about the world is shaped by the paradigm through which we choose to view it. The Freudian approach (which, with some justice, Chater disapproves of) involved getting people to lie down on couches and ramble . Not surprisingly, it generated an elaborate and convoluted model of the human mind. The experimental approach which Chater favours involves highly controlled experiments in which a single variable is manipulated and some other very specific variable is then measured. There are many advantages of this kind of methodology but, since it quite deliberately excludes almost all of the multidimensional complexity of the thing being studied, I don’t find it suprising that it results in the impression of flatness. Or an illusion of flatness, we might call it.

Novacon

I’m feeling very chuffed and… well… honoured, to be the Guest of Honour at this year’s Novacon in Nottingham. More details here. It runs from 9th-11th Nov.

I’m feeling very chuffed and… well… honoured, to be the Guest of Honour at this year’s Novacon in Nottingham. More details here. It runs from 9th-11th Nov.

New Covers

It’s a cliche that you can’t judge a book by its cover but in my experience the cover can make quite a difference to the whole reading experience. So I’m really delighted that Corvus have decided to re-release the first four novels of mine they published in these really beautiful new covers by Richard Evans.

Here are the three Eden books:

And here is my first novel, The Holy Machine, which has already had several very different cover designs:

And here is my first novel, The Holy Machine, which has already had several very different cover designs:

America City in paperback

Here’s the new cover for the paperback version of America City. It will be out on Sept 6th, and can be preordered now.

Here’s the new cover for the paperback version of America City. It will be out on Sept 6th, and can be preordered now.

Jali

I’m very pleased to be part of this original audio collection of six SF stories, which have just been published by Audible. Most of my books, including my latest short story collection Spring Tide, are available as audio books, but this is the first time that I’ve had a story whose first appearance was in audio format.

I’m very pleased to be part of this original audio collection of six SF stories, which have just been published by Audible. Most of my books, including my latest short story collection Spring Tide, are available as audio books, but this is the first time that I’ve had a story whose first appearance was in audio format.

My story is called ‘When Will We Get There?’ (the title being a deliberate homage to one of my very favourite stories, Philip K. Dick’s ‘I Hope I Shall Arrive Soon’), and it is beautifully read by Clare Corbett.

The other five stories in the collection are by An Owomoyela, Nikesh Shukla, Lauren Beukes, Ken Liu and Paul Cornell, so I’m in distinguished company.

Tintoretto

My wife Maggie and I recently spent a few days in Venice. Extraordinary place. It’s has been going round in my head ever since, even in my dreams, like some kind of mystery my brain is trying to solve.

But leaving all the rest of it to the side, here is just one thing we saw there which in itself keeps going round in my head. It’s in the church of San Giorgio Maggiore, on the island of the same name (which you can see across the water if you stand outside the front of the Doge’s Palace) and is a painting of the Last Supper by the Venetian Renaissance artist, Tintoretto.

The original is getting on for six metres wide, so you need to make this picture as big as as your screen can make it if you are to get any sense of it. The thing that struck me at once, not even knowing yet who the artist was (I am no art buff), was the drama and almost eerie immediacy achieved by the arrangement of the figures and by the sharp contrasts between light and shadow. I suppose by far the most well-known picture of the Last Supper is the famous mural by Da Vinci, which is at least as dramatic as this one in terms of what is going on between the characters, but nevertheless seems to me (on the basis of reproductions) to be much further removed from the viewer, much cooler and more static.

The original is getting on for six metres wide, so you need to make this picture as big as as your screen can make it if you are to get any sense of it. The thing that struck me at once, not even knowing yet who the artist was (I am no art buff), was the drama and almost eerie immediacy achieved by the arrangement of the figures and by the sharp contrasts between light and shadow. I suppose by far the most well-known picture of the Last Supper is the famous mural by Da Vinci, which is at least as dramatic as this one in terms of what is going on between the characters, but nevertheless seems to me (on the basis of reproductions) to be much further removed from the viewer, much cooler and more static.

What I get from this painting is a powerful sense of what a mysterious, explosive, dynamic thing a moment is. Everyone in this picture is present at the same point in time, but no two of them have the same sense of what is going on. A couple of disciples towards the left of the picture, for instance, seem to be involved in a conversation of their own that may not even be connected with the famous event unfolding in the middle of the table (an event to be re-enacted over and over again for the next two millenia, including on the altar immediately below where this picture is hung!) The disciple immediately to Jesus’ left seems withdrawn into his own throughts as he watches, perhaps to avoid having to engage with Judas sitting opposite him. Judas, as jealous people passive-aggressively do when trying to undermine someone else’s big occasion, seems to be trying to draw into conversation the disciple being given bread by Jesus. The waiters are getting on with their various jobs: at the near end of the table one of them is asking one of the disciples whether he wants anything else and the disciple is very clearly indicating with both hands: ‘Not now. Something important is happening.’ The semi-transparent angels meanwhile swirl above the scene, drawn in by what (within the terms of this story, obviously) they already know is an event of cosmic significance. Everyone is experiencing this moment in a different way, so that it will explode outwards into the future in many different directions, but, in this instant, they are all in one room, and the same light falls on all of them.

Venice is full of huge Tintorettos. There are lots of them in the Doge’s palace (including some incredibly detailed and energetic battle scenes, which I admired but was not particularly moved by). And the Scuola Grande di San Rocco has two whole floors of them. Most of these didn’t do much for me, I have to say, but they build up to a gigantic, twelve metre-wide Crucifixion in a side room on the top floor which rivals, and perhaps surpasses, the Last Supper for sheer energy. (Again: you need to make this image as big as you can to get any sense of it: it’s packed with detail.) As with the Supper, everyone is seeing different things and many are completely missing the famous drama going on immediately above their heads, but it is a single moment nevertheless, and the whole thing blasts out at you like an exploding bomb.

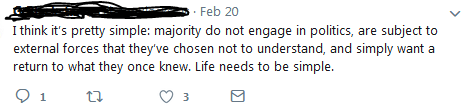

Trust

In this article, John Harris makes a point that I have made here a number of times ( a monotonous number of times, I fear) about the contemptuous dismissal by middle class liberals of those who had the audacity to vote against their wishes and preferences in the Brexit referendum of 2016 (another nice piece on this can be found here). As Harris points out, Leave voters, scolded for being lazily indifferent to evidence and suckers for simplistic explanations, are also frequently characterised as idiots and racists, even though this in itself is of course a lazy and simplistic generalisation. (But it seems it’s okay to make sweeping generalisations as long as it’s our side that’s doing it.)

Harris refers to an ugly and fatuous Venn diagram retweeted by Ben Goldacre (which is painfully ironic, given that Goldacre has made an entire career out of challenging lazy thinking, dodgy statistics and poorly reasoned claims). So let’s do a mental Venn diagram. Let’s start with a circle for Leave Voters and a circle for Remain voters. This is straightforward: the two circles are separate because you can’t do both.

If we were to add a circle for racists, it would of course overlap with the ‘Leave’ circle because disentangling oneself from foreigners is, on the whole, something that would appeal to racists. But, that being said, there’s no evidence to suggest that the ‘racist’ circle encompasses all or most of the 17m leave voters, or that plenty of racists didn’t vote remain. I mean, when you think about it, isn’t there something a bit racist about the idea of forming a powerful union of the predominantly white nations of Europe in order to shore up what remains of their former global dominance? The racist circle would certainly overlap with the leave circle, but it would overlap with the remain one too.

But now how about a circle representing voters who are less well off and more economically insecure? The evidence suggests that a larger part of this ‘left behind’ circle overlaps with the ‘leave’ circle, than overlaps with the ‘remain’ circle. (Of course a part of it overlaps with neither, because a lot of people didn’t vote at all).

On the other hand, a circle representing relatively prosperous voters -the ‘doing alright’ circle- overlaps more with the ‘remain’ circle, rather than the ‘leave’ one.

‘Ah,’ the doing alright remainers are prone to retort to this news-and I speak as a doing alright remainer myself- ‘but that’s because we’re the better educated and/or more able part of the population. Those left-behind people do not not understand the issues, and so are ruled more by prejudice, and are more easily duped.’

Yes, but we would say that wouldn’t we? It’s more comfortable for us than, say admitting that we voted for a status quo that has looked after us pretty well, or admitting that many leave voters may have voted the way they did because they were fed up with a status quo that (under Tories and Labour alike) hadn’t served them particularly well at all. It’s certainly more comfortable than admitting that a lot of us didn’t show much interest in whether they were doing well or not.

‘But can’t they see they’d be even worse off under Brexit?’ now howls the chorus of doing-alright remainers. Well, let’s leave aside how unappetising it must be to vote on the basis that ‘this lot will screw me over, but they might screw me over a bit less badly than the other lot.’ Let’s consider instead the possibility of drawing another circle, which represents those who understand how the economy really works. How big would that circle be? Would you be in it? And if you say you’d be in it, what exactly do you mean by that? Do you mean you really understand how the economy works, or do you mean you’ve read some articles which made sense to you, and were written by people you trusted? I’m certainly not in that circle, and, considering that I’m fairly bright and pretty well-educated, and passed my A-level in economics with a A, I do wonder how many people really are. In fact, I’m actually not sure that anyone is. (Ask yourself how many people predicted the crash of 2008, or what happened to that complete collapse of the Eurozone that pundits were predicting in the early years of this decade? Or consider whether there are any questions at all on which all economists agree in the way that, say, all biologists agree on the essentials of evolution?)

All of which is not to say that there is no such thing as economic expertise, or that experts are a waste of time, but rather to make the point that even professional economists are a very long way from certainty, and the rest of us form our views not on the basis of our own detailed understanding of how the economy really works, but on who we choose to trust. In that respect, I suggest, remainers are not so different to leavers as they may like to think. And I’d also suggest that ‘left behind’ folk would not be thinking in a wholly irrational way if they declined to believe experts who told them that the continuation of the status quo was in their interests.

What I keep coming back to is that no one wins elections by insulting the majority of the electorate. Politics (as I tried to portray in America City and Mother of Eden) is about doing deals. It’s about different groups in society, who may not have all that much in common, nevertheless entering into alliances with one or another. If you lose an election it makes no sense at all to blame the voters who didn’t support you, because you need to win at least some of them over to your side. The side that lost is the side that failed, the side that was trusted the least. It should be looking at itself to find out what it was doing wrong and what it could do differently, not casting around for scapegoats.