It’s always a big moment when I hold the book in my hands for the first time, and I love what Corvus has done with Spring Tide. My 21 stories are no longer just words, no longer just pixels on a white screen. They are a physical object which looks good and is satisfying to hold. There’s something magical about that, and it never seems to fade.

It’s always a big moment when I hold the book in my hands for the first time, and I love what Corvus has done with Spring Tide. My 21 stories are no longer just words, no longer just pixels on a white screen. They are a physical object which looks good and is satisfying to hold. There’s something magical about that, and it never seems to fade.

Category: All posts

The Epistocrats

I learnt a new word the other day: ‘epistocracy’. It means rule by experts.

It seems to me that -and I’m obviously painting with a very broad brush here- episocrats are already one of the two main ruling classes, the other being what I will call barons.

Barons derive their power from their position at the summits of pyramids of patronage. Historically barons controlled large estates and functioned as military leaders. In some countries (Myanmar, North Korea) these days the barons are generals, but elsewhere they may be bankers, industrialists, owners of media empires. If they are Russian, for some reason, we call them oligarchs.

Epistocrats derive their power from the utility and/or market value of their expertise. They are journalists, civil servants, academics, doctors, lawyers, engineers, computer scientists, biomedical researchers, inventors, legislators. They manage things, they create and propagate new knowledge (including ideological constructs that function as knowledge), they run the government, the media and the judiciary. (And, coming from a family of doctors, lawyers and academics, I am very definitely a member of this class.)

For the purposes of argument, let’s call the rest of the population the Plebeians. They’re the ones who don’t sit at the top, or even near the top, of patronage pyramids, and don’t have the particular kind of expertise that would place them in the epistocracy, whether because they don’t have the specialist education required (it typically takes many years of schooling to create an epistocrat), or because they lack the ability to make use of such an education. (It’s a fact not often discussed, but we are not all born with the same intellectual faculties.)

While epistocrats know a lot and have been trained to think in complex ways, plebeians, without that training, probably rely more on heuristics such as religion, tradition,’common sense’, ‘what everyone thinks’, tribal loyalty of some kind, or reliance on trusted authority figures. (Having said that, I need to qualify it immediately by stressing that (a) there is no reason to assume that such heuristics are necessarily always inferior as a guide to action than expert judgement, and (b) members of the epistocracy also rely a great deal on heuristics of these kinds, including tribal loyalty, ‘what everyone thinks’ and submission to authority, perhaps much more than they realise. But all that’s for another discussion.)

I’ve thought for a long time that sooner or later there would be a reaction against the epistocracy, not only because it is a relatively privileged class, but because the hegemony of the epistocratic world view threatens and undermines more traditional sources of meaning. What first got me thinking about this was the rise of fundamentalist Islam in the 80s and 90s, but it always seemed to me only a matter of time before something similar happened in other parts of the world. A successful uprising against the epistocracy formed the backdrop to my first novel, The Holy Machine, represented, admittedly somewhat simplistically, as a worldwide uprising of religious fundamentalisms of various kinds against science*.

But right now we are witnessing a real life revolt against the epistocracy in many parts of the planet. That really is what ‘populism’ is, isn’t it? A kind of politics that dismisses the intellectual frameworks within which politics have hitherto been practiced and appeals instead to those old heuristics such as religion, ‘common sense’, tribal loyalty.

To be accurate, what I am calling a revolt against the epistocracy is a revolt against a section of the epistocracy (for the revolt itself has epistocrats among its leaders.) But historically, a large part of the epistocracy has allied itself politically, at least to some degree, with the plebeians -the two groups had common interests in their struggles against the barons- and considered itself to be politically on or towards the ‘left’. For many epistocrats, I assume, such an alliance was more attractive than the alternative of being the intellectual handmaidens of the the barons. (It certainly is to me.) In my new novel America City, members of this left-leaning but privileged class are referred to as delicados.

But nowadays, this section of the epistocracy, the epistocratic left, the delicados, is the group that is now characterised by populists as the Liberal Elite, and their claim to be on the side of the plebeians is being called into question. I don’t know who wrote the following. It came to me from an aggressively populist source on twitter (‘I hate lefties… Can’t stand political correctness… Brexit…. Make America Great Again…’ etc etc) and while there are many respects in which it is unfair and dishonest, it seems to me to illustrate pretty well the kinds of charges that are laid, with at least some degree of justice, against the liberal epistocracy in Britain:

It’s a massive generalisation obviously, but, as I’ve said before, I think the liberal epistocracy has somewhat lost interest in the plebeians , preferring to direct its social conscience elsewhere. The tweets below, which I noticed and saved in the immediate aftermath of Britain’s vote to leave the European Union seemed to me at the time to be symptomatic.

These two tweeters’ concern for their East European cleaners is of course perfectly understandable. These are people they know personally and are fond of, nothing wrong with that, and of course there is no justification for such people to be bullied in the streets. But the wail of ‘THIS HAS GOT TO STOP’ struck me as terribly revealing. It isn’t directed at anyone. It isn’t in the second person. It doesn’t even refer to the offenders in the third person, but rather to the xenophobia itself as if it was some kind of alien force that has appeared from nowhere.

Yet there had been widespread unease about the scale of immigration for some time. For instance, the Migration Observatory at Oxford University [2011] found that ‘the preference for reducing migration is a majority view among virtually all segments of British society’, including ethnic minority groups, although its prevalence was highest among white British people, poorer people, less educated people and older people. Another for instance, and a fact that no one seemes to remember: In the last Euro-elections in 2014, UKIP won more seats in the European Parliament than any other British party.

I suggest that liberal epistocrats (myself included) behaved as if all of this could be ignored because it wasn’t to our liking and we assumed that people like us had sufficient power to make it go away. And now we’re finding out that wasn’t so. A revolution is going on, not against the barons, but against us.

And it seems to me that, like many a threatened ruling class before it, many liberal epistocrats are failing to grasp the new situation, failing to see the political adjustments they need to make. Instead of recognising that their alliance with the plebeians is important and in urgent need of renewal -important to us, I mean, as well as to the plebeians- I see many liberal epistocrats turning on the plebeians with contempt and anger. Brexit voters are called ‘thick’. Trump voters are called ‘deplorable’. Both groups are dismissed as racist and sexist by people whose anti-sexist and anti-racist creditentials may indeed be shining, but whose own classism is increasingly apparent**. (The word ‘thick’ is particularly revealing, if you think about it. If it’s not okay to mock someone for being disabled, how is it okay to show contempt for someone for not being educated or not being bright?)

In the wake of the Brexit vote, voices could be heard among the epistocratic classes saying that this was simply the wrong result and that parliament should ignore it. (The referendum was ‘only consultative’, apparently, though no one ever seemed to mention this until the vote was counted!) I have come across liberal Americans saying that those who voted for Trump are so vile and unforgivable that they don’t even want to try and win them back. (Good luck on winning without any of them!) And there are even voices these days that say that ignorant and uneducated people should be deprived of a vote. I see, for instance, that a book by an American academic came out in 2016 (I have to admit I’ve not read it) which argued that democracy should be replaced by epistocracy in its literal sense: nations should be governed not by the representives of the people as a whole but, like Plato’s Republic. by the knowledgeable.

Well, there’s always been a strand among liberal and leftwing folk that thinks ordinary people must be told what to do for their own good. Lenin, for instance, introduced the idea of a ‘vanguard party’ of professional revolutionaries who would exercise the dictatorship of the proletariat on the proletariat’s behalf.

Of course, he thus created a new ruling class that (via Stalin, purges, famines and the gulag) transformed itself at length into the capitalist oligarchy we know today, having long since jettisoned any trace of the ideology which the vanguard party was formed to serve.

I think myself that’s the sort of thing that tends to happen when any group of people decide they can’t share power and that the world should be ruled exclusively by people like themselves. Either that, or they are crushed completely.

*My novel Marcher, and the short stories from which it evolved, also explored this theme.

**Two points here. (1) Given that attitudes now recognised as sexist and racist were mainstream a generation or two ago, it’s always going to be the case that the least educated part of the population will seem sexist and racist compared to the most educated part. This is actually quite convenient for members of better educated elites who would like to have both the moral high ground and the benefits of their privileged position. (2) It is perhaps not surprising that relatively well-to-do, educated elites might prefer to foreground social divisions like gender, race, sexual orientation, ability/disability, which cut across social classes, and pay less attention to social class itself. I recently heard the Vice-Chancellor of Oxford University being questioned on the radio about her enormous salary. A harsh edge came into her voice and she barked back (from memory), ‘I hope the BBC isn’t suggesting that I don’t deserve the same salary as my male predecessor’. More comfortable to identify as a member of a disadvantaged gender, than as a member of a privileged class.

Time for Cakes and Ale: Podcast Interview

Here’s a podcast interview with me, by ‘Time for Cakes and Ale’ run by Becks and Eeson. They describe their podcast as ‘an outlet for our ramblings on whatever geeky topics take our fancy’. I like a bit of rambling myself, and here they have indulged me at length. Thanks both.

Getting into Writing (Interview with Zeroflash)

Interview here, mainly on the process of writing and getting published. Thanks Zeroflash!

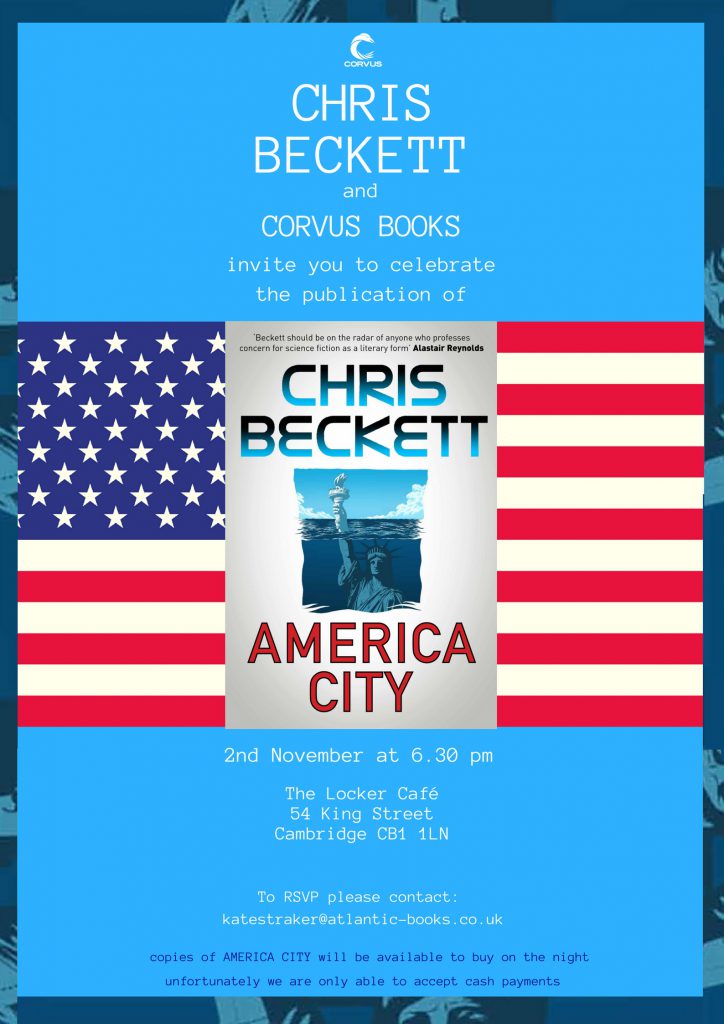

Launch of America City, Nov 2nd

If in or near Cambridge on Nov 2nd, do come to the launch of America City at the delightful The Locker Cafe on King St. (Please RSVP to Kate Straker as per invite below, so she has an idea of numbers)

Feed (Words I don’t like #3)

Here’s another word I don’t like: ‘Feed’, used in the internet sense, as in ‘there are a lot of angry people in my Twitter feed today.’ It always jars when I come across it. But the odd part in this case is that it’s actually quite an expressive word to use. What grates with me, now I think about it, is its use in an unironic/uncritical way.

In fact I’d go as far as to say that, if nobody used it in this unironic way, I might choose it myself. It has a suitably industrial and impersonal feel. It makes me think of a machine that dispenses food pellets at timed intervals to animals in a battery farm. If had not already been stripped of those connotations, it would do the job pretty well.

See also Problematic (#1), Heft, Grin (#2)

Words I don’t like #2

There are some words that I think of as typical creative writing words and have never liked. Words that, to me, say, ‘Hey look at me, I’m writing!’ I’ve never liked the word ‘heft’, for instance, as in ‘he felt the heft of it in his hand.’ It means ‘weight’ doesn’t it? Why not just say ‘weight’? No one says ‘heft’ in ordinary speech.

Another one, very unfairly, is ‘grin’, used as a more interesting alternative to ‘smile’. A perfectly ordinary word, I know, and I do choose it occasionally if I find I’ve used ‘smile’ too often, but I really don’t like it and put ‘smile’ wherever possible. ‘Grin’ feels to me, for some reason, like one of those words you fall back on in desperation when you’re trying to bring alive a character on the page who doesn’t even feel alive in your head.

The fire from the skies

When I was a kid at school in the 70s a lot of the music we listened to was blues-based stuff and prog rock. I don’t listen to much of that now -the music from then that stands the test of time for me is from quite different genres- but here is a little prog rock classic that still works for me: the extended piece by Genesis called Supper’s Ready. I specially love the section that breaks out at about 15:30 in a burst of sheer exultant energy, with imagery straight from the Book of Revelations:

With the guards of Magog, swarming around

The Pied Piper takes his children underground

Dragon’s coming out of the sea

Shimmering silver head of wisdom looking at me

He brings down the fire from the skies

You can tell he’s doing well by the look in human eyes

Better not compromise, it won’t be easy

666 is no longer alone

He’s getting out the marrow in your backbone

And the seven trumpets blowing sweet rock and roll

Gonna blow right down inside your soul

Pythagoras with the looking glass reflects the full moon

In blood, he’s writing the lyrics of a brand-new tune

Why is it that the destruction of everything we know can be such an exhilarating idea? Is too fanciful of me to say that being human is only one thin layer of what we are, and that (as the Jeff folk put it in Eden) before anything else, we are simply the world looking out at itself? From that perspective, after all, nothing can ever be finally destroyed, only thrown in the fire to be cast anew.

What SF is good for

There is a lovely review of Mother of Eden here. The reviewer, Kevin Elliot, writes ‘”Mother of Eden” is a prime example of how science fiction can handle issues which might pose problems for other genres.’

Well, I’m not the one to say whether Mother of Eden is a prime example of that or not, but I completely agree with him that science fiction is the ideal medium for exploring certain kinds of issue. As I have said elsewhere, science fiction differs from conventional realist fiction in that, while the latter holds the world constant but makes up characters and situations, science fiction makes up the world as well. This means that, while realist fiction is rich in potential for thought experiments about human psychology and human relationships, science fiction offers additional options for thought experiments about society, social structures and social change. The Eden books, for better or worse, are one such experiment.

The realist author takes the existing world (present or past) as given, in other words, but engages in the game of ‘what if’ with characters and their interactions, while SF writers can also engage in ‘what if’ games in relation to the world as a whole. In the case of Eden, I asked myself, ‘what if society evolved all over again from two individuals.’

I’m talking about potential here. Not all science fiction carries out such experiments – the SF pack of playing cards can be used for many different games – and, of course, when it does, it doesn’t necessarily do it well. But this is true also of the realist pack of cards.

Heil Trump!

We have had neo-Nazi marches before, in Europe and America. But here is one where marchers are chanting the name of the US President as if he were their leader. That, surely, is unprecedented.

Video: Alt-right marcher shouting "Heil, Trump" while waving nazi salute

via @tomperriello #charlottesville #AMJoy pic.twitter.com/s3MMSxEhWe

— Scott Dworkin (@funder) August 12, 2017