I’ll be at Worldcon 75 in Helsinki next week, and I’ve been asked to take part in a panel on ‘Write Long and Cut, or Write Short and Add? (Is it better to write as much as possible and then edit out, or vice versa?)’. If you’re at the con, I hope I’ll see you there! In the meantime, here are a few thoughts:

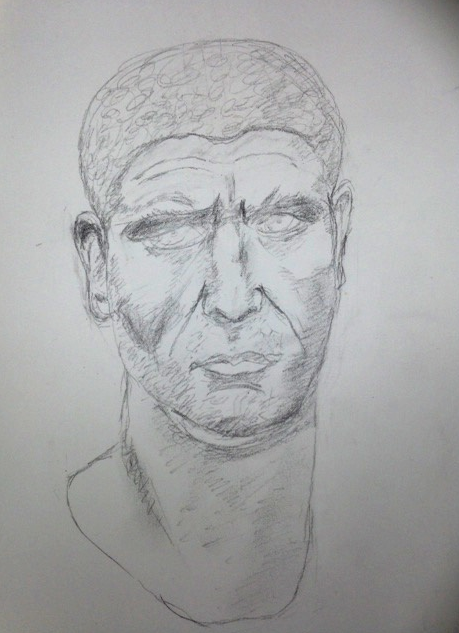

I’ve been doing a bit of drawing lately (one of my recent efforts is below) and one of the things I’ve learnt about that is that you need to be careful to get the basics right before you commit too much to the detail. If you are drawing a face for example, no amount of detail will make the picture look like its subject if the overall shape is wrong. The temptation is to get too engrossed in, say, the shadows around the eyes, only to realise later on that the eyes are too close together, and that at least one of them will need to be rubbed out completely and drawn all over again.

(Roman Emperor, Philip the Arab, drawn at Museum of Classical Archaeology, Cambridge)

(Roman Emperor, Philip the Arab, drawn at Museum of Classical Archaeology, Cambridge)

When writing fiction, there is a similar danger of over-committing to detail at too early a stage. This can result in beautifully crafted scenes which turn out not to fit in, but which you are reluctant to cut because you like them and have committed a lot of time to them: a lot more time can be wasted trying to make the book fit the scene rather than vice versa.

A big difference between drawing from life and writing fiction, though, is that there is no external object to act as a guide: you are not trying to reproduce something in front of you, but rather you are tapping into your knowledge, experience, and subconscious to create a new object that didn’t previously exist. Quite often, the overall shape may actually emerge out of details.

My novel Daughter of Eden, for instance, only came alive for me when I decided to tell the whole thing from the point of view of Angie Redlantern, and for that to happen, I first needed to bring Angie alive for myself by working over scenes told in her voice. Similarly, early drafts of The Holy Machine felt to me they were missing a certain something until I worked out how to write the opening pages. In both cases it was the detail of the voice, and how that voice described its world, that were the key to the entire book. I could have drafted out all the plot outlines I liked, but without knowing how the story was to be told, they wouldn’t have come to anything.

So it is a matter of writing something that vaguely resembles the story that I want to write, or the beginning of that story, and then working and reworking the material until it starts to feel lively. I always start a writing day by revising what I wrote on the previous day, and not infrequently I will go right back to the beginning and revise everything I’ve written so far before carrying on. It’s slow, but it seems to be necessary in order to dig myself down into the story.

As to whether to ‘write long and cut, or write short and add’ I don’t have a straightforward answer. What I’ve noticed is that, as a piece of writing develops, my sense of the centre of gravity of the piece gradually changes and I start to notice what I think of as expansion points and contraction points. In early drafts of the first half of Daughter of Eden, the story was told from multiple viewpoints like the other Eden books and Angie was simply one of several main characters. As I worked and reworked it, I decided Angie was to be at the centre of it, and that all the foregrounded characters were going to be women (Angie, Mary, Trueheart, Starlight and Gaia), while the stereotypically ‘male’ story of war and fighting would be pushed some way back into the mix.

So expansion points are places in the text which seemed of relatively minor importance to start with but are now more important, perhaps to the point where they now feel like the story. In some cases, material which was little more than a connector between two scenes, can turn out to be more important than the scenes themselves. One set of expansion points in Daughter of Eden concerned the Davidfolk’s rituals around circles and the idea of homecoming. That stuff was just a detail at first, one of those things you put in to make a scene a bit more concrete, but it became absolutely crucial to the overall shape of the book, and so I expanded and developed all that, not only by including more detail (the circles, the song, the dots on the foreheads of guards…), but by incorporating those ideas and beliefs into Angie’s thinking.

Contraction points, on the other hand, are places in the text whose importance, or necessity, has diminished over time, so that they need cutting back, or cutting out entirely. In the case of Daughter of Eden this included scenes seen from the viewpoint of male characters, some of which I cut altogether, while others were shortened and retold as observed by Angie, or reconstructed by Angie thirdhand from stories told by others, or relayed by Angie from scenes that Starlight participated in and told her about.

So I suppose my conclusion from all this is, write what you can, and be prepared both to expand and cut.