Interview here with Tom Hunter, of the Clarke Award.

Category: All posts

How I write

My friend Tony Ballantyne has been asking writers to describe their writing process, posting the results on his website every month. Here is what I wrote for him.

If you haven’t encountered Tony’s work, I recommend it. He is one of the cleverest people I know, in fact quite possibly the cleverest. (I won’t embarass him by saying that, by the way: he doesn’t really do that kind of humility.) Annoyingly, apart from being a talented and productive writer, having a degree in maths, and being a deputy head of a secondary school, he also plays several musical instruments and is a member of a brass band. His novels are unlike anything I’ve ever encountered. However there is something about his particular vision, dark, witty, humane, and occasionally tinged with a rather scary version of Christian theology (the latter particularly apparent in Recursion), that occasionally reminds me of Philip K. Dick.

His latest novel is Dream Paris -full of strange Ballantynian angles on the French revolution and politics in general- but you’d probably do better to read Dream London first.

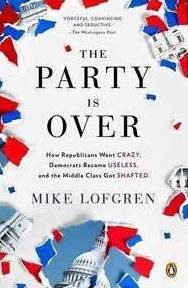

The Party is Over

Already long ago, from when we sold our vote to no man, the People have abdicated our duties; for the People who once upon a time handed out military command, high civil office, legions — everything, now restrains itself and anxiously hopes for just two things: bread and circuses (Juvenal, c100 CE: Satire 10.77-81)

A public that pays more attention to reality TV than its status as free citizens cannot withstand an unremitting encroachment on its liberties by calculating, unscrupulous and power-hungry leaders (Mike Lofgren, The Party is Over, 2012 CE)

I haven’t even finished reading this book yet, and I may well have more to say about it later. It is packed with sharp, pithily expressed and extremely scary observations about the break-down of the American political system and its corruption by corporate money. A Republican who worked as a staffer in Congress for nearly 30 years, Lofgren is pretty scathing about the Democrats, but his most bitter attacks (at least so far) are directed against his own party which he describes as becoming less and less like a political party and more like ‘an apocalyptic cult’.

What he really exposes is a kind of doublespeak in which strident claims to be defending something – the constitution, liberty, democracy, the national interest- are used to conceal attacks on that same object. ‘Let us now dispose,’ Lofgren writes, for instance, ‘ of the quaint notion that the present-day Republican Party is conservative.’ He defines the GOP, as it now exists, as a ‘radical right-wing party’, which doesn’t really conserve and protect anything, for all that it invokes the memory of a romanticised past, but seeks to completely transform society in the interests of the very wealthy* using whatever means possible and with a kind of Leninist ruthlessness.

The American political system works in a very different way from the British one, but there is much here that is familiar to a British reader all the same. For instance:

The GOP reflexively scorns so-called elites (by which it means educated, critical thinkers) to mask the way it is utterly beholden to the true American elite.

I am particularly struck by Lofgren’s observation that the current Republican Party deliberately seeks to undermine the credibility of government itself:

Should Republicans succeed in preventing the Senate from doing its job, it would further lower Congress’s favorability rating among the American people. In such a scenario the party that presents itself as programmatically against government – i.e., the Republican Party – will come out the relative winner.

Undermining Americans’ belief in their own institutions of self-government remains a prime GOP electoral strategy.

A UK parallel is the relentless attack on the quality of public services, which is always ostensibly in the name of making them better, but which in fact reduces the standing of the services themselves. But we also have a culture of cynicism about politicians and government in general, and I’ve long thought that (for instance) leftish comedians should be more aware of whose interests such routine and unfocused cynicism actually serves.

*Interesting fact: according to Lofgren under Eisenhower’s Republican presidency in the 50s, the top rate of income tax in the US was 91%. Even the new leadership of the British Labour Party, characterised by many as unelectably left-wing, only proposes a top rate of 50%.

Marcher on offer

The violent faith

The grail legend has always had certain hold on my imagination since I encountered it as a child, and I’ve often thought about using it in some way in a story. Partly for that reason, and partly because I’m perennially fascinated by the way that stories evolve over time, I recently read a translation of the original grail romance by Chretien de Troyes and then an interesting book* by Richard Barber which looks at how the story has changed over the centuries. It was a bit of an eye-opener.

One point that Barber makes is that the original grail stories were written for a particular audience. These tales of knightly valour were written for real-life knights and, like so many books still do, served the purpose, among others, of flattering their readers. For instance, looking at the original de Troyes story, and at the extracts of other medieval versions cited by Barber, I was struck by the amount of bling involved. You are constantly being told about the beautiful and costly possessions of the knights and ladies in the story, and being reminded that such things are their due as members of the gentry.

More chillingly, in one early thirteenth century version of the story (The High Book of the Grail), we are reminded of the business of those real life knights:

…the Good Knight went out to scour the land where the New Law [i.e. Christianity] was being neglected. He killed all those who would not believe in it, and the country of was ruled and protected by him, and the Law of Our Lord exalted by his strength and valour. (Barber, p 51)

The High Book was dedicated to Jean de Nesle, a leading figure both in the brutal Fourth Crusade against Constantinople, and in the Albigensian Crusade against the Cathars that followed . I happen to have also read a book** recently about the latter. Ordered by Pope Innocent III, it involved (among other things) the massacre in 1209 of the entire 20,000 population of the town of Beziers.

* * *

All this came back to me when, reading the commentary around David Bowie’s death, I was reminded that there had been some controversy about Bowie’s ‘blasphemous’ use of Christian imagery in his video for ‘The Next Day’. And I was particularly struck by a comment of the former Archbishop of Canterbury, Lord Carey: ‘I doubt that Bowie would have the courage to use Islamic imagery. I very much doubt it’.

What a strange and revealing remark. People like Bowie wouldn’t mock Christianity, he is really saying, if they thought they might be killed for it. And Carey should know! His own Anglican church is the largest denomination in the English-speaking world, after all, not as the result of kindly Episcopalians gently persuading Catholics and others of the error of their ways, but through the use of violence and terror. Read Hilary Mantel’s Cromwell novels for a description of a process which included, among other things, monks who refused to swear allegiance to Henry VIII as head of the English church being publicly castrated and disembowelled.

* * *

Yes, and in the same way, the reason that there are no Cathars today in the South of France is not that the Roman Catholic church engaged in rational argument with that version of the Christian faith, treating its beliefs with respect, and showing the kind of sensitivity to the feelings of its adherents that Bowie was told off for failing to exercise. No. Cathars were hunted down, tortured to make them inform on one another, and burnt alive until their entire faith was completely exterminated. In one case, the Catholic authorities learned that an elderly woman had asked for the Cathar equivalent of the Last Rites. She was taken from her death bed and thrown onto a fire.

The versions of Christianity that we know today are actually only a small subset of the ones that have existed in the past, and the Cathars are only one example of the alternatives that were annihilated by the violence of their more ruthless or more powerful rivals. It’s interesting to consider what kind of effect this Darwinian process has had on the content of Christian belief itself. For a religion, too, is a story written for the benefit of an audience, and this religion, in the form we know it —the form that now asks for its feelings to be respected—was written for generations by or for those who regarded killing and torture as legimate ways of treating those who disagreed with them. Lord Carey’s strange comment suggests to me that he and his church have a long way to go before they fully recognise the implications of that. It reminded me of a husband telling his wife she ought to be more grateful that he doesn’t beat her any more.

*Richard Barber, The Holy Grail: the history of a legend. Penguin.

**Stephen O’Shea, The Perfect Heresy: the life and death of the Cathars. Profile Books.

The stories of stories

I’ve always loved the way that stories themselves have stories, changing and evolving over time, so I liked the the idea reported here that some of the traditional fairytales we all know may go back many thousands of years. The research which the article refers to uses similar techniques to those used by biologists and linguists to trace stories back to common ancestors, and concluded, for instance, that ‘the story known as ‘the Smith and the Devil was estimated to date back 6,000 years to the bronze age’. (A smith sells his soul to the devil, but then outsmarts him: I’d say that the song ‘The Devil went down to Georgia‘ is an example, albeit with a fiddler instead of a smith.)

But I reckon some stories must go back a lot further than that. There’s a Native American story from the Northwest coast of North America about a magical, shape-shifting Raven who stole fire, as well as the sun and stars, for humankind, who until then had lived in cold and darkness. This is surely strikingly similar to the story of Prometheus in Greek myth, who also stole fire for humankind*.

But how far back would you have to go back to find a cultural common ancestor of Greece and pre-Columbian America?

*Prometheus stole fire from the Gods, while Raven stole from an eagle. But it was eagles that were sent to punish Prometheus. There is also a Norse story, in which Loki, a subversive shape shifter like Raven, steals from the giant Thiassi and escapes in bird form. The giant pursues him in the form of an enormous eagle, and dies when fire sets light to his feathers. (Raven is scorched too: his feathers used to be pure white, but are turned black by the fire he stole.)

His own peculiar complex illness…

The BBC’s current serialised adaption of War and Peace made me look back at my copy of the book. I’d quite forgotten that, when reading it some years ago, I’d made a note of a number of authorial reflections and asides which particularly struck me, the very things that are inevitably lost when a work as massive as this is transferred to the screen. Here was one (I hope it’s not too much of a spoiler to reveal that Natasha gets ill!):

Doctors visited Natasha both singly and in consultation, spoke a good deal of French, German, and Latin, denounced one another, prescribed the most varied medications for all the illnesses known to them: but the simple thought never occurred to any of them that they could not know the illness Natasha was suffering from… for each human being has his peculiarities, and also his his own peculiar complex illness, unknown to medical science, not an illness of the lungs, the liver, the skin, the heart, the nerves and so on… but an illness consisting in one of the countless combinations of afflictions of these organs*.

A constantly recurring theme in the book -it’s particularly evident in the discussion of the war, which repeatedly contrasts what actually happened, with how this rationalised after the event- is the chaotic nature of life, the way that at any given moment of time we are faced with a unique and incredibly complex set of circumstances which we can’t possibly fully understand, and which will have changed in any case in the next moment, and the next and the next. Doctors, generals, military historians, intellectuals, are all at various points depicted as persuading themselves that they can understand and master what is in fact unmasterable.

In historical events what is most obvious is the prohibition against eating the tree of knowledge. Only unconscious activity bears fruit, and a man who plays a role in a historical event never understands its significance. If he attempts to understand it, he is struck with fruitlessness.

In their own way, those doctors were useful, though not at all in the sense that they imagined:

They were useful not because they made the patient swallow what were for the most part harmful substances . . ., but they were useful, necessary, inevitable, because they satisfied the moral need of the sick girl and the people who loved her. They satisfied that eternal human need for the hope of relief, the need for compassion and action, which a human being experiences in a time of suffering.

I think a lot of this stuff struck me at the time -in fact, I believe this was why I made those notes- because of its relevance to my former profession of social work, which, just like Tolstoy’s doctors, attempts interventions again and again in complex, unique and ever changing situations which can’t really be truly understood, in order to satisfy the “moral need” of society to feel it is doing something about the troubling people on its fringes.

In War and Peace, the arrogance of Napoleon, who does not understand the limitations of his knowledge or power, and imagines himself as so godlike as to be able to impose his own will on events, is contrasted with the wisdom of General Kutuzov, with his minimalist approach that was always ready to retreat or give ground and let events take their course, even when others were insisting that “something must be done”, if this seemed likely to result in those events unfolding in roughly the right direction on their own. The best social workers understand this, but like politicians, and like general Kutuzov, they are constantly up against the false logic of the “Politician’s syllogism”**:

- We must do something

- This is something

- Therefore, we must do this.

*Translation by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky, published by Vintage Books, 2007

**First spelled out like this in the satirical TV programme, Yes, Minister.

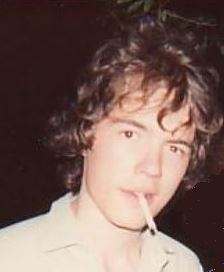

David Bowie

I was 15 when Hunky Dory came out, and it completely enchanted me. Lush, lavish, at times almost operatic, it was wonderfully different from the earthy bluesy music people around me were listening to at the time, and I couldn’t get enough of it.

So taken with David Bowie was I, in fact, that I actually risked expulsion from school to see him. Discovering that he would be playing at Oxford Town Hall one Saturday night, as part of his Ziggy Stardust tour, I bunked off from the boarding school I was at in Dorset, and hitchhiked 70-odd miles to Oxford. I was an odd, solitary kid at that time and had run off from school on a previous occasion to wander for four days round the Dorset countryside by myself, oddly indifferent to the worry I was causing. It had been made pretty clear to me that, if I went missing like that again, the school would ask me to leave.

Bowie still wasn’t famous enough then to fill a town hall, and I just bought a ticket at the door. I sat in one of those brown metal chairs with canvas seats that you get, or used to get, in village halls, with empty seats all around me. It was a fairly ragged performance as I remember (perhaps simply because I missed the lushness and artifice of Hunky Dory) but it was certainly a spectacle. Bowie was in full Ziggy Stardust regalia, kneeling to perform musical fellatio on the guitar strings of his beautiful blonde guitarist, Mick Ronson. (I wonder if his biggest achievement might turn out to be that he opened up the possibility that gay sexuality could be stylish and cool? But I think the pull for me was the way that he made loneliness and outsiderhood seem cool also.)

Although Oxford was actually my home town, I didn’t think my parents would appreciate the fact that I was playing hookey from school, so after the concert I spent the night on the streets. When it got too cold in the early hours of the morning, I huddled up in a cubicle in a public toilet. (A trick I’d learnt from the previous escapade was to sleep in the Ladies. The Gents had urinals that suddenly flushed every few minutes, jerking me out of whatever level of sleep I’d managed to reach.)

When dawn broke, I hitched back down to Dorset. I guess this was about 4 or 5 in the morning. I remember the first driver to pick me up was so tired that he nodded off and drove right over a roundabout rather than going round it. Luckily there was no other traffic on the road.

Back at school I’d got someone to ruffle up my dormitory bed to make it look like I’d slept in it, and no one had noticed my absence. This was probably a good thing, because my happiest time at that school was my final year, and I made some friends then who’ve remained friends to this day.

Though who knows? Perhaps if I’d been expelled, I would have been forced to have the showdown with my parents that I really should have had, but which boarding school – and perhaps this is one of the purposes of this peculiar English institution – had helped me and them to sidestep. In which case Bowie really would have changed my life. As it was, a previous Bowie album, The Man who Sold the World, darker and more druggy, was to become the soundtrack to my memories of a time when, in place of open rebellion, I and my new friends retreated into our own subterranean world.

Here’s a Bowie song (actually a cover by him of a song by Iggy Pop), from a much later period, which is associated in my mind with that feeling of freedom and breaking away that comes with a sudden impulsive journey.

Daughter of Eden

The next and final Eden novel will be called Daughter of Eden. (No publication date has been finalised as yet.)

As in Mother of Eden, the events in Daughter of Eden take place more than two centuries on from the events in Dark Eden, but on the opposite side of the great rift in the human society of Eden that occurred in the original book.

Mother of Eden was about Starlight Brooking’s experiences among the descendants of those who followed John Redlantern. Daughter of Eden will follow Starlight’s childhood friend Angie among the Davidfolk, the descendants of those who remained loyal to John’s great enemy, David Redlantern.

Angie, who left her home to be become a shadowspeaker, will be present at two cataclysmic events that change the course of Eden’s history.

I think this book is the best thing I’ve yet done.

New interview

A new interview here with Science Book a Day, which is run by George Aranda in Melbourne, Australia. The interview is mainly about Dark Eden .