Another good evening at Sferakon yesterday.

Here’s a further extract from the Croatian scene in The Holy Machine:

Help came in the form of a solitary figure in black hurrying across the square. It was an elderly widow, tightly clutching an enormous brown cockerel in both arms.

‘What kind of monastery is this?’ I asked her. ‘Who is it dedicated to?’

I must have spoken something that at least approximated to her own language. She stopped and looked at me.

‘You poor boy! You must go in! The monks are good. They will give you help.’

‘But what kind of monks? Who do they believe in?’

‘They are kind and holy. They’ll help you.’

‘Please,’ I grabbed her arm. ‘Please tell me. What do they believe in?’

She stared at me. Something in my face shocked her. She released the cockerel’s neck, so as to free her right hand to cross herself.

‘It is a monastery of the Roman Church,’ she said, ‘but now that it is given over to the Holy Machine, may the Lord bless his name, who knows what church it belongs to.’

The cockerel, red wattles quivering, had twisted his neck round to stare at me with a fierce yellow eye. It suddenly emitted a loud, cold shriek.

‘The Holy… Machine?’ I mumbled.

‘Yes.’ She gave a little laugh. ‘A great miracle. He is a kind of robot, but God has given him a soul – and not an ordinary human soul either, but the soul of a saint or an angel!’

‘But… I thought robots were… bad…’

‘Yes, of course, and Mary Magdalene was a whore. To God, all things are possible.’

The woman smiled and patted me on the arm.

‘Go in, young man. You’ve got a fever. They’ll get you dry and give you something to eat.’

A sudden eruption of activity and noise made me cower and cry out with fear. But it was just the cockerel. It had worked one of its wings free and was beating it frantically.

‘No you don’t!’ snapped the old woman, grabbing it grimly by the throat.

‘Go in,’ she urged me over her shoulder as she dealt with the offending bird. ‘Go in!’

The rain was starting up again. She hurried on.

* * *

Even just the time I had spent standing and talking with the widow had left my body stiff. I hobbled very slowly across the square, only to quail in front of the blue double door. Here was food, warmth, rest. Here more importantly than anything was the possibility of forgiveness that had been the whole purpose of this journey. Somewhere within was that bright, silver being that I so longed to meet. But now I dreaded that encounter.

Very reluctantly I lifted my hand to the knocker. A stab of pain ran through my body. I let the knocker fall.

Thud!

Silence.

Silence.

A cold gust of wind blew the rain across the empty square.

I give up, I thought. Let me just crawl away to some hole in the ground and sink peacefully into oblivion.

I had already turned away from the door when from within came the sound of sliding bolts. The left half of the big door slowly opened to reveal a small, fat, balding monk.

‘I am…’ I hesitated for a moment before I could recall my own name. ‘I am George Simling, an Illyrian. I wondered… I need food, somewhere to sleep. I want to see the Holy Machine.’

‘Come in then, come in.’

* * *

And then I found that the closed door was already behind me and I was in a pale, stone-flagged corridor. The monk took my arm. There were many small blue doors down one side. I caught a glimpse of a bright tree glistening in an empty courtyard. Then many more doors.

I felt myself coming to from a labyrinthine dream of mountains, wars and roads… I woke up and remembered that reality was simply this: moving slowly along a corridor with calm blue doors. On and on. That was life. Why bother to open the doors? Why bother? Why not just carry on along here? It would be fine if it wasn’t so cold. It would be just fine.

I came to again. There were voices. Another monk had appeared, this one tall and sandy-haired. The two men were conferring about me. I couldn’t understand the words at first. I think I was trying to listen to them in the wrong language.

A blue door opened. I was a little afraid. But I went up into the sky and looked down from above, as if into a doll’s house.

In a small bare room with a single chair and a single bed, a monk was talking to a pale young man with bleeding feet. (‘Not him again!’ I thought. ‘Why is it always him?’)

‘Take off your wet clothes,’ the monk coaxed gently, ‘We’ll get you some dry things and something to eat, and we’ll dress these feet. Then you must rest. You have a very high temperature indeed.’

Another monk arrived. Another little monk down there in the doll’s house with miniature dressings and a tiny bowl of water.

‘We’ll have to undress him,’ said the first one. ‘I don’t think he can do it for himself.’

‘Are you sure he speaks Croatian?’

‘Yes. Well he spoke it clearly enough when he arrived. His name is George. He’s from the City.’

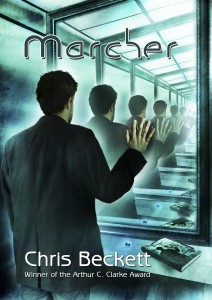

I just received a copy of the new Marcher today from Ian Whates at NewCon press. It’s always a lovely feeling, that first time you put your hands on the actual physical book. And I love the cover image by Ben Baldwin, loosely based on the famous painting by Magritte: ‘Not to be reproduced’.

I just received a copy of the new Marcher today from Ian Whates at NewCon press. It’s always a lovely feeling, that first time you put your hands on the actual physical book. And I love the cover image by Ben Baldwin, loosely based on the famous painting by Magritte: ‘Not to be reproduced’.