James Salter’s first novel, and the only book of his that I’ve read, was originally published in 1956. It’s about American fighter pilots in the Korean War, a transition point in aerial warfare, when the planes were jets with swept-back wings, but still fought each other with guns, as the fighters of WW2 had done.

James Salter’s first novel, and the only book of his that I’ve read, was originally published in 1956. It’s about American fighter pilots in the Korean War, a transition point in aerial warfare, when the planes were jets with swept-back wings, but still fought each other with guns, as the fighters of WW2 had done.

I bought the book after reading an article on Salter in the LRB by James Meek, which observed that twentieth-century American novelists tend to depict the military as victims, but that The Hunters had more in common with the Iliad or Beowulf than with Catch-22. In this book, aerial warfare is not depicted as a cruel waste of young men, but as a kind of princely sport. Salter himself was an USAF officer for some time, and was a fighter pilot in the Korean War – he himself shot down a MIG fighter above the Yalu River – and his attitude to this experience is evident in his preface to the 1997 edition:

It was said of Lord Byron that he was more proud of his Norman ancestors who had accompanied William the Conqueror in the invasion of England than of having written famed works… Looking back, I feel a pride akin to that in having flown and fought along the Yalu.

All this is very remote from my own experience, my own stance on life, my own temperament, and my own sense of what I’m capable of, physically, emotionally, morally. I dislike war and the readiness to resort to war as a means of solving problems. I seldom win at competitive games. I’ve worked most of my adult life in a profession in which women outnumber men by eight or nine to one. But I nevertheless found myself interested in this book about an exclusively male world in which hunting down MIGs is

… a child’s dream and a man’s heaven, living a medieval life under sanitary conditions, flying the last shreds of something irreplaceable, I don’t know what, in a sport too kingly even for kings.

The only strand of connection I have with this world is that I was fascinated by fighter planes as a child. I owned many books about them. I loved to see them in the sky, and, when I had the chance, to go and look at them close up, their silvery riveted wings, their cramped cockpits filled with mysterious dials, their sleek forms made unspeakably glamorous by their association with speed and power and death.

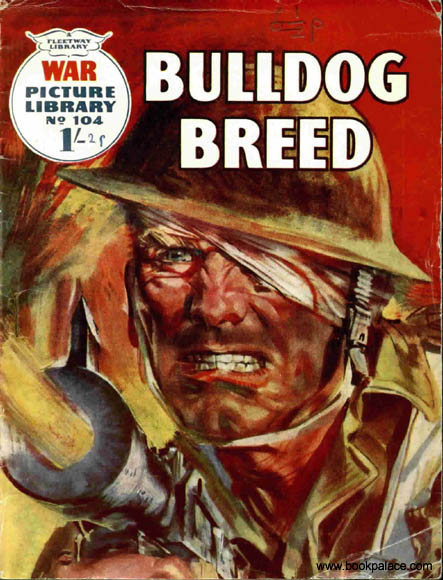

Another thing I remember from my childhood was a form of comic book that we used to refer to as ‘war mags’. They were a kind of graphic novel, I suppose, or graphic novella anyway. I don’t remember ever actually buying one, but they were passed about at school and I must have read dozens of them, each one containing a single story about British soldiers or airmen in World War II, fighting against the Germans (who said things like ‘Britisher schweinhund!’) or the Japanese (who said ‘Banzai!’). There were a lot of blazing machine guns and grim-faced men, but fighting the enemy was always the backdrop to a more personal story about male relationships. As I recall a typical plot involved rivalry or even bitter hatred between two men, or perhaps two groups of men, who were supposed to be fighting on the same side. A happy ending might be the resolution of this conflict, and a new friendship, or at least a new respect, ‘forged in the white heat of battle’, or alternatively the death of a real bad egg, paying the price of his own lack of courage, or integrity, or loyalty to his mates.

Another thing I remember from my childhood was a form of comic book that we used to refer to as ‘war mags’. They were a kind of graphic novel, I suppose, or graphic novella anyway. I don’t remember ever actually buying one, but they were passed about at school and I must have read dozens of them, each one containing a single story about British soldiers or airmen in World War II, fighting against the Germans (who said things like ‘Britisher schweinhund!’) or the Japanese (who said ‘Banzai!’). There were a lot of blazing machine guns and grim-faced men, but fighting the enemy was always the backdrop to a more personal story about male relationships. As I recall a typical plot involved rivalry or even bitter hatred between two men, or perhaps two groups of men, who were supposed to be fighting on the same side. A happy ending might be the resolution of this conflict, and a new friendship, or at least a new respect, ‘forged in the white heat of battle’, or alternatively the death of a real bad egg, paying the price of his own lack of courage, or integrity, or loyalty to his mates.

The Hunters, it seems to me, is essentially a literary war mag. The plot centres on the rivalry between Cleve, the main viewpoint character, who desperately longs for ‘kills’ but somehow keeps failing to be in the sky at the right moment, and Pell, a shallow and selfish man who is quite prepared to place his comrades’ lives in jeopardy in his pursuit of the five MIGs that will make him officially an ‘ace’.

At one point, Cleve is on the tail of a MIG and about to make a kill when Pell radios for help: he’s being pursued by MIGs and is unable to extricate himself because, when he tried to jettison his disposable fuel tanks, one of them got stuck and is now hanging half off, impairing his manoeuvrability. Cleve, honourably, abandons the chase to rescue him, even though he’s desperate to add a second kill to his solitary success. Pell subsequently shakes off his drop tank and goes on to claim the destruction of another MIG as his crucial fifth kill. Basking in glory back at base, he crowns his ingratitude and dishonesty by insinuating that Cleve, the man who gave up a kill to save him, is a coward who avoids a fight.

All this is pure war mag, it really is, but I guess that the world evoked by war mags wasn’t entirely a fantasy, and that Homer wasn’t making it all up when he wrote about those fierce and competitive warrior-princes. A particular kind of grouping, held together by a code of honour, and driven by a very clear and very narrow definition of success for which its members are willing to risk everything, really does exist, and really is one of the many ways in which human beings manage to imbue their lives with meaning. There are odder things, after all. There are people whose entire life is organised around the need to get a bicycle round a circular track a fraction of second faster than anyone else.

Salter’s sparse, Hemingway-like prose works well, writing about men who are not in the habit of discussing their emotions and would regard it as sissy to wax lyrical about beauty. Occasional, carefully rationed outbursts of lyricism are all the more effective for emerging from out of this Spartan restraint, particularly the evocations of those mysterious landscapes of cloud and air, far enough above the ground to be separate worlds, which are the medium through which the pilots fly and seek their enemies. Salter’s sudden, temporary viewpoint shifts, too, going against all the usual rules, are daring and interesting and worth studying as a technique. The war mag plot is sometimes rather predictable – when a pilot’s longing to get home to his wife and sons is described in more detail than any other pilot’s homesickness, or when a gun camera is jammed at the beginning of a mission so that there will be no photographic evidence of any kill, or when a legendary MIG pilot known as Casey Jones puts in an appearance on the enemy side, you just know what’s going to happen next – but it drives the book forward and keeps you turning the pages, just as it did in the war mags themselves.

War mags never had women in them. Here, the few women characters, described almost entirely in terms of their physical attractiveness to the men, are entirely marginal figures – they include barmaids, waitresses , prostitutes, and one young Japanese woman who very briefly becomes an object of romantic yearning – but I guess this is may be realistic, in a novel written from the perspective of the male pilots. When you focus exclusively on a single narrow objective, presumably editing out as far as possible the horror of the deaths you cause or may suffer yourself, your grasp of the rest of the world must indeed become attenuated, utilitarian and shallow. Cleve half-grasps this himself, though much of the time he seems to accept that this narrowness of vision, and the risk of a horrible death, are prices worth paying for those solitary existential moments among the clouds, hunting and being hunted.