Someone quoted the following quite widely-cited passage from M John Harrison in something I read recently:

‘Worldbuilding is dull. Worldbuilding literalises the urge to invent. Worldbuilding gives an unnecessary permission for acts of writing (indeed, for acts of reading). Worldbuilding numbs the reader’s ability to fulfil their part of the bargain, because it believes that it has to do everything around here if anything is going to get done.

‘Above all, worldbuilding is not technically necessary. It is the great clomping foot of nerdism. It is the attempt to exhaustively survey a place that isn’t there. A good writer would never try to do that, even with a place that is there. It isn’t possible, & if it was the results wouldn’t be readable: they would constitute not a book but the biggest library ever built, a hallowed place of dedication & lifelong study. This gives us a clue to the psychological type of the worldbuilder & the worldbuilder’s victim, and makes us very afraid.’ [More context here]

Do I agree? Well, it depends what kind of worldbuilding he means. Some worldbuilding is necessary to any sort of story-telling – all stories need a context of some kind, and sometimes the context is at least as important as any of the characters – but some worldbuilding isn’t necessary in that way, and too much of it can be counterproductive, even if it doesn’t make us ‘very afraid’.

Of course Harrison is right that for a writer to construct a whole world is in any case impossible. Even to precisely describe a wooden chair would take more words than the word count of an entire library of novels. The reader must be allowed to do much of the work (work to which we are well accustomed, since in life also, we must assemble a sense of a complete world from a collection of fragments and guesses.)

Harrison’s own novel The Sunken Land Begins to Rise Again is actually, I’d say, a rather good piece of worldbuilding. The story ostensibly takes place in contemporary England, partly in London and partly in the Midlands, but the setting is an imaginary place nevertheless, and one of the main pleasures of reading the book, and the thing that most lingered in my mind afterwards, is this place’s peculiar, queasy, dreamlike flavour. (The one moment that jarred for me was when the narrator mentioned ‘the debacle of Brexit’, thus ceasing to be the unfolder of a fictional world and becoming just M. John Harrison talking about this one.)

The Sunken Land is saturated with watery imagery: flooded fields, flooded houses, flooded gardens, dampness, houseboats, phials of muddy water, things that live in water, the River Thames, the River Severn, taps, kettles, toilets, a map of the oceans, the pools that form in sodden fields where you can still see grass and flowers beneath the glassy surface… This squelchy stuff, which all of us can easily assemble in some form or other from our own watery memories, comes together in the book to form an extended metaphor for the main protagonist’s depressed, sunken state (and, in a less clearly defined way, a metaphor also for the country we live in), so it’s absolutely essential to the whole enterprise that we enter into it. But he coaxes us to do this, not by precisely describing and explaining everything, which would be impossible (as he says), but by convincing us that he has immersed himself in it.

Lots of novels fail to do this. I have given up reading many books because I can’t experience their settings as anything more than clumsy cardboard cutouts, which no one has ever really inhabited. And if even the author hasn’t been there, why should I as a reader even try? But my point here is that this is worldbuilding, and there wouldn’t be much left of The Sunken Land without it.

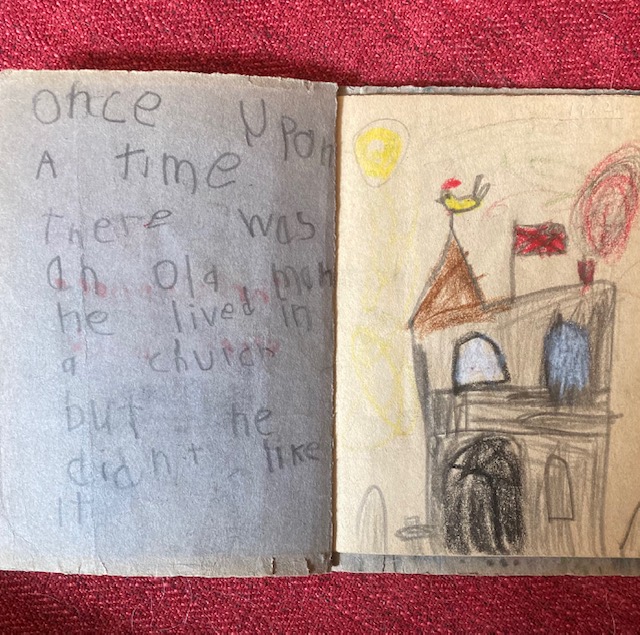

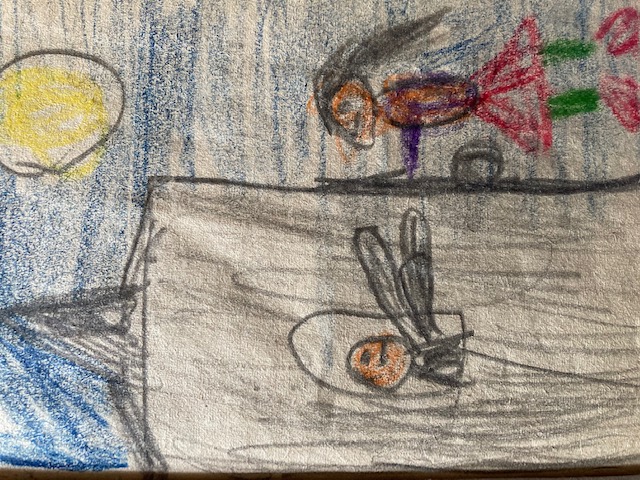

What Harrison dislikes, then, is not worldbuilding per se, but a particular kind of worldbuilding in which the author gets over involved in making stuff up for the sake of it, fussily providing piles of detail which have no thematic purpose and get in the way of our own imaginations. The classic case of this is Tolkein’s imagined languages, alphabets and the whole vast historical/mythological backstory he created for the Lord of the Rings (though, to be fair, he summarised much of this material in appendices to avoid overloading the books themselves). Tolkein clearly had fun coming up with all this detail and, since I used to make up languages, alphabets and mythologies myself as a kid, I understand the pleasure of it. It’s the sort of activity that feels comfortable and safe because it’s intellectually engaging but also emotionally neutral, a bit like doing crosswords, or sorting out a stamp collection, or playing solitaire on your phone. (These days I look things up on Wikipedia that have no bearing on anything important to me at all. I find it restful.)

I don’t myself see anything sinister in this sort of activity, but it certainly doesn’t have much to do with story-telling, or the literary arts, and most of us probably wouldn’t want to feel that we’d spent too much time on it at the cost of other more lively and more outward-looking pursuits. It can be an escape from stress, though, and readers as well as writers find it so, which is where the ‘nerdism’ comes in. Some people enjoy absorbing themselves in the minutiae of imaginary worlds such as Tolkein’s, or J K Rowling’s. Some people learn to speak Klingon, or enact scenes from their favourite fictional universes, taking a holiday from the real world in those non-existent places. The kind of worldbuilding that Harrison disapproves of is (I think) the construction of these sorts of intricate non-places to hide in, something that is often referred to as escapism by those who dislike science fiction and fantasy.

I’m sort of with him. Yet at the same time I think it can be a hard line to draw, this line between necessary worldbuilding, which Harrison’s novel is a good example of, and the escapist kind which he despises and which, as he puts it, is not ‘technically necessary‘. After all, any novel or story, however literary, however serious, however engaged with painful and important topics, is necessarily in part an escape from the quotidian world, for writer and reader alike. Even a discussion such as this is in part a nerdy escape of that kind. Even the learned arguments that take place amongst eminent critics and distinguished scholars.