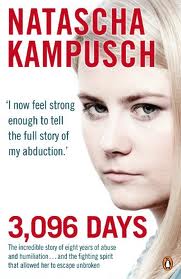

The tabloid-sounding quote on the cover is misleading. This is a serious and thoughtful book, by a young woman who was kidnapped by a stranger at the age of 10, and remained his captive for the next eight years.

The tabloid-sounding quote on the cover is misleading. This is a serious and thoughtful book, by a young woman who was kidnapped by a stranger at the age of 10, and remained his captive for the next eight years.

It is very disturbing to read. At times I found the claustrophobia hard to bear, even at second hand. For the first six months Kampsuch was confined in a small hidden underground room, which could only be accessed through three doors, the last one made of concrete, which were so elaborately locked and concealed that it took her kidnapper, Wolfgang Priklopil, an hour to get through them all each time he came to visit her, and an hour again to seal it all up again when he left. At weekends, when Priklopil had his mother to stay, Kampsuch was down there alone for three days at a stretch. One of her fears was that he would have an accident and never return for her.

Gradually, Priklopil began letting her out for limited periods, making her work for him as a slave, and even taking her on trips outside the house. He became increasingly violent towards her, lashing out at her with fists and with hard objects without warning. He shaved her head. He kept her chronically weak with hunger. He forbade her from talking about her family. Yet he also kitted out her dungeon like a girl’s bedroom, with desk, a bunk bed, a computer, fetched her books and magazines at her request.

What is striking about the book (apart, of course, from the story itself) is the firm, clear, individual voice in which it is written. Kampusch refuses to view Priklopil simply as a monster, or herself as a helpless victim, whatever the pressure from the media and society to do so:

The perpetrator must be a beast so we can see ourselves as being on the side of good. His crime must be embellished with S & M fantasies and wild orgies, until it is so extreme that it no longer has anything to do with our lives.

And the victim must have been broken and must remain so, so that the externalization of evil is possible. The victim who refuses to assume this role contradicts society’s simplistic view. Nobody wants to see it. People would have to take a look at themselves.

She says that her refusal to reduce this story to thriller-like categories of black and white, but to insist on shades of grey, has led to her being criticised and subjected to abuse on the internet. But she is absolutely firm on it. In particular she angrily rejects the idea that her ability to see Priklopil as not all bad, is a symption of the Stockholm Syndrome. She hates this label, which she says victimises her all over again, and she insists that her behaviour was essentially rational. Priklopil was the only human being she had contact with for eight years, and she made of that the best that she could.

Her firmness in rejecting the stock narratives that others try to impose on her story, is matched by her small acts of resistance to Priklopil himself. He demanded she call him ‘maestro’, or ‘my lord’, and tried to get her to kneel in front of him, but she steadfastly refused, knowing that it was essential that she hold something back. Somehow, this young woman (she is still only 24, a year younger than my own oldest daughter) managed to hold on to a sense of integrity in these appalling circumstances.

Naturally, when reading the book, one identifies with Kampusch. The appalling claustrophobic loneliness, the miniscule scope for manouevre, the constant anxiety, the fear for the future: for many of us, it isn’t entirely alien territory, for unhappy times in any childhood feel a bit like this: helpless, trapped, alone, cut off from what you need or long for. (The comparison of everyday unhappiness with this ordeal may seem grotesque, but it is one that Kampusch herself makes, reflecting on her own lonely and unhappy childhood before her captivity.) These claustrophobic feelings are ones that most of us are familiar with, I imagine, to some extent, and it is uncomfortable to be reminded of them, or to have to imagine them in the unbelievably extreme form that Kampusch herself endured.

But even more disturbing is to consider Priklopil in the light that Kampusch shines on him. Her insistence on not making him a horror-movie monster, is very powerful, forcing the reader to consider him not as something utterly ‘other’, but as a person on a continuum with the rest of us. Priklopil, as she sees it,

…didn’t want anything more than anyone else: love, approval, warmth. He wanted somebody for whom he himself was the most important person in the world. He didn’t seem to seen other way to achieve that than to abduct a shy, ten-year-old girl and cut her off from the outside world until she was psychologically so alienated that he could ‘create’ her anew.

Kampusch refers to the Greek legend of the sculptor Pygmalion, who didn’t like women, but fell in love with the idealised woman he’d carved in stone. Attempting to meet needs for intimacy by trying to bully or manipulate others into playing roles that we have assigned to them: it’s hardly unique to Priklopil.

Images of the cellar room where Kampusch was confined, from BBC News.

Images of the cellar room where Kampusch was confined, from BBC News.