“I’d pestered and pestered to be allowed outside to play in the fine scatter of snow and eventually my mother gave in. She packed me into my red snowsuit, fastening the zip so high that it caught my throat. Then she escorted my outside and positioned me on the patio. My eyes were awash with unshed tears as my father called, ‘Say cheese.’ Afterwards, when I wanted to play they said it was too cold and made me come straight back indoors. They have forgotten this. It is something that has been… unremembered. They refer to the photograph as ‘that lovely picture of you having fun in the snow.'”

“I’d pestered and pestered to be allowed outside to play in the fine scatter of snow and eventually my mother gave in. She packed me into my red snowsuit, fastening the zip so high that it caught my throat. Then she escorted my outside and positioned me on the patio. My eyes were awash with unshed tears as my father called, ‘Say cheese.’ Afterwards, when I wanted to play they said it was too cold and made me come straight back indoors. They have forgotten this. It is something that has been… unremembered. They refer to the photograph as ‘that lovely picture of you having fun in the snow.'”

In 2010, I was one of the judges for the Edge Hill Short Story Award. As well as the main prize, which is given for single-author collections (that year it was won by Jeremy Dyson for The Cranes that Build the Cranes), we were also asked to give an award for individual short stories submitted by students on Edge Hill University’s creative writing programme. This proved to be an easy task, for we were all immediately agreed that the most outstanding submission was a story by Carys Bray that began:

“I have been looking for a baby to borrow for a number of weeks. I’ve offered to look after several, even some I don’t know very well. But their mothers seem suspicious. I ask nicely. I say please and I smile. I remember to ask if it’s a girl or a boy and how old it is, although I’m more interested in its length than anything.”

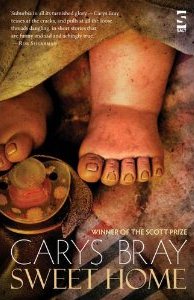

The story, ‘Just in case’, is included in this new collection from Salt, along with 16 others. They are all more or less about domestic life. Many of them, like ‘Just in Case’ are downright dark, and others are sad and bleak. A dementing old women in ‘My burglar’ hides her possessions in strange places because she is convinced that a burglar comes in the night, and their resulting absence then becomes more evidence of the threat, and a reason to hide yet more things. The ‘Wooden mum’, worn out by the incessant crazy-making demands of her autistic son Tom and the cruelly underming ‘help’ of her mother-in-law, reflects on the moment when Tom was born, and she imagined herself the happiest woman in the world. A father in ‘The Rescue’ waits outside the flat of his heroin-addicted son in a concrete corridor in a tower block, for someone from somewhere to come and rescue him, as those Chilean miners were rescued from underground.

But this book is not just an orgy of bleakness and despair. The quote I started with cames from a story called ‘Love: terms and conditions’. It begins with a woman visiting her parents with her husband and three children, and being reminded of her own wretched childhood, but it ends with an account of how she has managed nevertheless to achieve for her own children ‘a family where love doesn’t track a base rate of obedience’ (what a brilliant line!). You can see this is hard for her, you can see that sometimes she tries too hard – at one point, remembering how she wasn’t allowed to play in the snow, she tries to get her reluctant children out of their warm beds to come out and enjoy the snow in the middle of the night – but she has succeeded. Life is often sad, and that can make us afraid to tell hopeful stories for fear that we are sugar-coating the truth, but this story really earns its happy ending.

It’s a difficult thing too, I think, to write about family life, which unlike wars and love affairs and murders and all the other staples of fiction, does not tend to come with a beginning, a middle and an end, but follows a daily cycle, on and on for years. But it’s a trick that Carys Bray pulls off in various ways. The final story in the collection, ‘On the way home’, works like a relay race in which the baton is passed on from family to family. In the final scene, a little girl called Anna realises that her mother is fed up with her for grazing her leg and making a hole in her tights. “The mild rebuke presses a slump on Anna’s shoulders. Mummy is disappointed again.”

Her mother tells her to wait while she goes into a shop. When she comes out again, she is holding a lollypop in a bag.

“‘ Don’t worry about the tights, sweetheart. That looks sore. Does it hurt?’

“‘A bit,’ Anna admits.

“‘I know something that always makes people feel better,’ Mummy says. She hands the lollypop to Anna. Then she crouches on the pavement of Bridge Road and places winter-cool lips on the exposed cap of Anna’s knee where it pokes through the hole in her tights, round as a biscuit.

“And on the nobble at the base of Mummy’s neck, in the delicate fuzz of hair, Anna places a soft, dry kiss of her own.”

What a great ending. It made me wonder why literature deals so little with such kisses, and treats them so lightly on the whole, and yet deals so often with, and treats so very seriously, the quickly fading kisses of romantic love.