I find it quite difficult to immerse myself in a novel these days and often have to make myself keep turning the pages. (I don’t know whether is this me getting more fussy as I grow older, or whether perhaps it’s the business of writing fiction that makes it harder: I imagine a puppeteer finds it hard to surrender to the illusion of a puppet show). But never mind all that because I did find this book immersive, and read the whole thing very quickly and greedily.

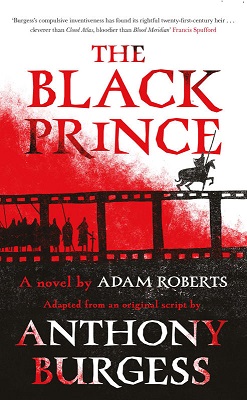

This is a novel written by Adam Roberts, drawing on a film script and some notes by the late Anthony Burgess. I have to say that, in my opinion, the least successful parts of the book were the various interludes in the main action in the form of ‘news flashes’ and ‘camera’s eye’ views. In incorporating these, Roberts was being faithful to Burgess’ plan to make use of story-telling tricks invented by John Dos Passos. However I found them an unwanted distraction, and not really in keeping with the rest of the book, so that each time they came up I was impatient to get back to the main narrative. This, by contrast, I found entirely gripping.

Edward the Black Prince was the son of King Edward III and would have have been Edward IV if he hadn’t died before his father. He is famous as a warrior, defeating French armies much larger than his own at the battles of Crecy and Poitiers, and as a kind of epitome of the chivalrous knight in armour. In fact, as this book shows, the wars he fought to expand and defend his father’s realms in France were incredibly bloody and brutal. In an age when ordinary people had absolutely no say in the decisions being made by their leaders, it was nevertheless considered perfectly acceptable, and perfectly consistent with the theological doctrine of ‘just war’, to hack to death the entire population of a town, including children and babies, if the leading figures in that town had chosen not to surrender promptly enough. (Since carpet bombing of cities remains a pretty standard weapon of war in modern times, I suppose we haven’t really changed in this respect. We just do our indiscriminate slaughtering from a sanitised distance which allows us to call it ‘collateral damage’).

The savage and gleeful butchery involved, particularly at the sack of Limoges, is described by Roberts in remorseless detail. I was going to say harrowing detail, but that actually wouldn’t be entirely honest, because the truth is (and I’m not proud of this, but I’m guessing I’m not alone) that I actually find this stuff quite engrossing, and even exciting, to read about. The end result was that I emerged from the book disturbed not only by the events described, but by my own troublingly ambiguous response. Which is surely as it should be, because these things are not perpetrated by monsters but by human beings, drawing on the same instincts, desires and fears as the rest of us.

On this same theme, Roberts does a great job of conveying the humanity of the Black Prince and the other characters, as they move between ruthless slaughter and the ordinary emotions of everyday life. A professional mercenary for example, who fights and kills for plunder, grieves over his much-loved wife and regrets that he didn’t treat her better when she was alive. Occasionally characters feel some unease about what to us seem their most obvious sins, the industrial-scale killings in which they’ve been engaged, but they are human beings and have all kinds of defences and justifications that prevent them from worrying about these things for too long, much as we have defences, I suppose, that prevent us from worrying for any length of time about the exploitative sweat shops where people build the digital toys we play with, or the dangerous mines where the minerals for them are extracted.

One strand that was particularly fascinating was the Black Prince’s preoccupation with the Holy Spirit, and what that meant. As I gather from other writings of his, Roberts is not a believer in the Christian religion but nevertheless finds Christian theology imaginatively engaging (a description that could be applied to me too and, from what I understand, also to Anthony Burgess). And it is by exploring this idea of the Holy Spirit that he lifts this book from being merely a grim catalogue of human cruelty into something more profound and even a little bit hopeful.