Richard Dawkins observed that every religious person is an atheist with respect to every belief system except their own. One could quibble with that, one could point out that, if we are to agree that this is so, his own particular conception of ‘atheism’ would need to be added to the list. But the point I want to make just now is that the same is true in politics.

Religious belief is not for most people a matter of free choice, but is closely tied to geography and to heritage. Go to rural Morocco, and you won’t find many Protestants but you will find plenty of people who sincerely believe in Islam. Go to the American Midwest and the reverse is true. Even when people consciously move away from the religion of their ancestors, they tend to do so as a group.

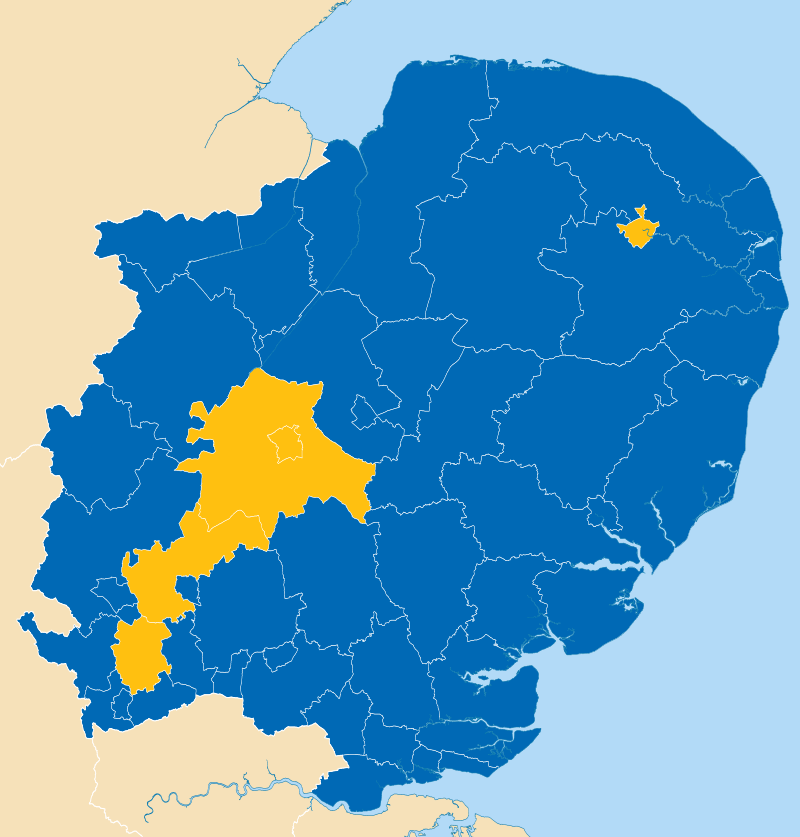

Support for different political ideas is also not randomly distributed across the country. There are Labour areas, Tory areas, and Liberal and nationalist areas, and there are also Leave and Remain areas. Below is the referendum result map for the East of England where I live. (Pretty solidly Leave except for the small Remain island of Norwich and the larger Remain island stretching south from Cambridge.)

I see politics as consisting of two levels. In its essentials it is the process by which different classes and groups in society jockey for position, with each class or group seeking to defend what its has and, if possible, improve what it has. However most human beings like to see themselves as good, and so every group likes to have a reason why its demands are not in fact self-interested but in the interests of everyone (and usually there is at least an element of truth in the claim). As I think of it to myself, each group flies a flag.

And, just as we see through every religion but our own, so we tend to assume that the flags flown by rival groups are either the product of delusion, or a cover for self-interest, but take our own flags at face value, and find it difficult to accept that we too might be deluded, or that we too might have chosen a particular flag because it justifies our own self-interest. Many Remain voters, for instance, argue ‘we must be right because we are clever and well-educated’, without recognising that clever and well-educated people have their own particular interests as a class.

The main protagonist of Two Tribes is a man, Harry, who, in the latter half of 2016 notices that his own group’s flag is, after all, just one of several flags. He doesn’t reject it, but he becomes suspicious of the claims his friends make for it. He meets a woman, Michelle, who, so to speak, lives under the enemy flag. Both of them are intrigued by this because in other respects they like each other very much.

The story is told by another woman, Zoe, who lives two and half centuries away in the future. The flags of 2016 are not quite as remote to her as, say, Yorkists and Lancastrians are to us, because they still have counterparts in her world. But she knows things that we don’t know about the way that the culture wars of the twenty-first century played out, and she looks back at the period in a way that isn’t really aligned with either the Remainer or the Leaver camp.

More on Two Tribes here.

Hi Chris, I really enjoyed Two Tribes which was a very interesting follow-up to your “US politics” novel, America City. I do have a bone to pick with you as a resident of Saffron Walden which is not a “Tory toytown” but has a rebel streak. We set up our own political party and thrashed the Tories in the last local election – the biggest swing in the country (see https://www.residents4u.org/about-residents-for-uttlesford/our-history/) if you are interested. Kind regards, Richard

I’m so pleased you enjoyed the book, Richard, and I apologise if I’ve done an injustice to your home town! I have nothing against Saffron Walden, I assure you.